Emerging Methodologies: LAB Fellow, Mike Kiley, Delves Deep

The Congress on Research in Dance (CORD), an organization dedicated to facilitating dialogue about and for dance professionals convened in Philadelphia just before Thanksgiving . CORD conferences take on various topics that usually center around a single theme. This year their website describes the content of the conference in the following way:

With this joint meeting conference with the Society of Ethnomusicology, we hope to forge pathways of (re)connection between dance and music that will prove long lasting and meaningful. By drawing attention to the multiplicity of sounds in dance and ways in which music moves its listeners, we aim to generate fruitful dialogue that will enable a regeneration of the relationships between music and dance scholarship.

This got me thinking about Michael Kiley, a 2011-12 LAB Fellow, who has already begun some magnificent research into this very topic. Recently he began developing some methodology around the creation of movement and music in an effort to seek a deeper connectivity between choreography and composition. With his permission, I am sharing his reflections on a weekend intensive he recently conducted at the LAB.

Please visit the CORD website for more information about their organization at www.cordance.org.

By Michael Kiley

By Michael Kiley

The first exploration of the marriage of original choreography and music during my LAB Fellowship was a two-day workshop with Kelly Donovan and Meg Fry of De Facto Dance (NY). I have chosen to work with several choreographers who approach dance making from very different avenues during my LAB time. De Facto creates their pieces largely through improvisation, and were students of Richard Bull. From my experience with them, I find Kelly and Meg to be very articulate about dance making, so I thought that working with them would be a good place to start my research.

Leading up to the workshop, I had sent both of them a series of questions in order to get us started. Here are some excerpts:

Me:

Could you briefly describe the role that music and sound has had in your work thus far?

Meg:

Since I’ve been thinking over the past couple of days about these questions, I’ve realized that music played a huge — fundamental — role in how we learned choreographic improvisation itself. Richard Bull often used musical ideas in order to generate movement ideas, and would structure pieces around the basic idea of movement following the changes in the music. We did an insane piece with him to Greggery Peccary, a Frank Zappa song, and I recall feeling a bit overwhelmed at having to match the high energy and particular, punctuated phrasing of the music. Cynthia Novak was a master at relating in a very detailed movement way to whatever music we were working with.

Of course, then Richard took it a step farther and started working with speaking as music — Radio Dances being a prime example. So that talking dances were in a way an extension of working with music.

Richard would also set an improvisational dance, and vary the music each time we did it, including sometimes on the night of the performance.

And, as we’ve all said/heard a million times, but it bears repeating here, choreographic improvisation is largely an idea that Richard took from jazz music and translated into dance.

Kelly:

Sometimes music is the inspiration for a dance. Sometimes I choreograph with a piece of music in mind, and then use something else for the performance. De Facto has played with switching music from performance to performance. Often, I have created mixed scores, on my own and/or with the help of a sound editor. Ambient sound is also important.

Me:

Have you ever used music that was not written specifically for your dances in a finished piece? If so, why? Were you concerned with the audience’s preconceived relationship to this music?

Kelly:

NO and YES, depending on what worked for a particular dance.

For a dance called “Into the Wild” – In one section we used a Mozart piece that went well under our talking score. It was relatively quiet with bursts of loud moments and worked well under talking. I always thought the music itself was both funny, serious and dramatic, yet low-key. We used this music because it worked well under talking and accentuated the feeling of the section – dramatic and funny. One viewer – a music buff – said he had never felt the humor in this particular piece of music before.

Meg:

Yes, we use music all the time that is not written for us. The latest example was The Heroic Diagonal, which Kelly directed for a cast of 14 — De Facto plus guests. I was worried about the strong, sentimental, sweeping quality of the music (kind of like a movie soundtrack) (Sufjan Stevens, BQE). I felt that it had no irony in it, and that we would seem pretentious and overly serious. But the fact was that working with that piece of music gave the dance a gravitas that De Facto’s work normally doesn’t have; we rose to the challenge of the music — a tribute to Kelly’s strong spatial choreography and the commitment of the dancers to really dance it.

For De Facto’s piece Cinderzilla, Kelly made a sound score using lots of different musical sources but combining them into a new original score. Richard used to do this as well. They both did/do this amazingly well. It has been more the norm for us to work with pre-recorded music rather than new original music.

****

When we arrived at the space, I had hoped to further discuss these questions, and explore some of these ideas…using music as an impulse for generating movement, changing music for certain dance structures, how to work with a song, etc. I also hoped to discuss what makes a piece of music “work” rather than not, and how do we know this?

We did a physical warm up first, and then I lead a vocal warm up, introducing the voice as one aspect of sound in a piece. I teach voice in terms of resonations, explaining that sound waves travel in the shape that they are made, or the shape that they resonate. I felt that talking about the shape of a sound wave might help when talking about sound for dance, as dance is largely about shape. Throughout this weekend, I would learn that a great way to understand the relationship between the two forms is to try and find the similarities between them: space, shape, tone, color, rhythm, etc. Music and dance are strangely similar in how difficult they are to describe, and therefore discussing the two of them can be even more difficult. One of my goals is to develop a vocabulary that both dancer and musician can understand.

The three of us then did a walking dance together. We discussed certain moments of the dance, and shared our general experiences together. I noticed that we often talked in terms of emotion rather than physically describing a moment. This would be come very important in our time together.

I found it amazingly helpful to improvise with these two choreographers. I experienced what I imagine all dancers experience, that of getting lost in the movement. There came a moment where I was simply playing with the way that my body can move, which as improvisers, is where a large part of De Facto’s work lives. We talked about how fun that can be. And how to translate that fun to an audience, realizing that this can be self indulgent at times, and if we would like our audience to connect to our work, we must find a way for the audience to get in. I think music plays a large part in creating this bridge between the experience of an improvising dancer and an audience member. It can often represent the movement sonically.

After the walking dance, we listened to five pieces of music and discussed what we heard. This was very helpful in the formation of a vocabulary for us to talk about music for the rest of our time together. Something that arose out of the walking dance and hearing these pieces was the idea of relative time: How time can feel like it is moving slowly at times, quickly at others, and how dance and music can do that to a viewer or listener. We as makers can then use this idea to try and affect our audience, through setting up a framework, and either sticking with it or breaking it. What I mean is, delivering on expectations created by a movement or musical phrase or not, by breaking it unexpectedly.

Kelly and Meg then improvised on the idea of trying to slow down and speed up time. How can we do this without it becoming predictable? When a phrase of music is played, it is finite. Same with a dance phrase. It has a beginning, middle and end, no matter how esoteric or nebulous. Because it is finite, we as audience understand that we have traveled a certain amount of time together and that we are either going to travel that distance again, or that it will shift. So how do we play with that expectation to positive affect? How can we use this information to let our audience get lost in time? Because we all agreed that the moments in performance, and in life that are most successful, are directly related to time and how it is being perceived. From drug use to falling in love, to having sex, to digestion, bathing, waiting, etc. Our perception of time seems related to our level of enjoyment as humans.

We wrapped up the day with Kelly and Meg “catching” solos that each other made. One of them would begin, and then the other would “catch” or take over the dance. It was really interesting for me to sit back and watch this process, as each dancer changed the improvisation just like adding a new piece of music to it would have. Again, drawing these parallels between music and dance seems helpful to me, at least for now.

The second day we invited four dancers, Nichole Canuso, Alex Romania, Mason Rosenthal and Amanda Hunt to join us. We started the day in similar warm up fashion, filling the dancers in on what we had been exploring.

Our walking dance lead to a discussion of improv versus set choreography. This of course directly related to improvised music and tightly rehearsed music. Meg mentioned something I thought was really interesting, that when she knows she has to remember a certain phrase, she finds that she “dumbs it down” so that she can repeat it. Only in improvisation does she relax that “dumbing down” instinct, and let go into a fuller form of movement, and therefore “the changes seem deeper.” She spoke to set movement getting deeper through repetition, not discovery. I found this a really interesting way to describe it, and that this statement exemplifies that wide way of thinking about creation, whatever the form. Certain dancers are excellent at retaining and recalling movement. Others aren’t. Certain musicians compose by improvising on their instrument, others by hearing things in their head. I’ve had people tell me that I am not a “true composer” because I usually write while sitting with an instrument, instead of a sheet of staff paper. This is obviously bull shit, but it highlights how different schools of thought in the dance and music world can really stifle one another by placing value on certain avenues into each form over the other. Perhaps there are choreographers out there that write off improvisational work because it doesn’t flex the same choreographic muscle that they do when they choreograph. I think that these biases are interesting, and should be paid more attention to by the dance and music communities as a whole. My best guess is that what makes a work successful versus unsuccessful has little to do with any of this. It has more to do with what is at the core of each piece, rather than the avenue into it.

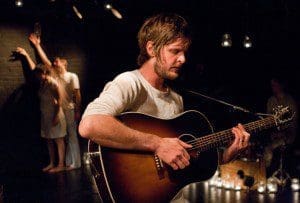

The theme of the impossibility of repeating something exactly the same way every time got unearthed somewhere during the weekend. So we decided to attempt to create a piece, based on an improvisational structure that Kelly created, dividing the dancers into two groups of three. We played with the impossibility of exact repetition and the stretching of time. We did this in silence the first time. We then repeated the structure with some formal changes, and added in the idea of resonating on vowels, playing with their voices in space. After it was finished, the dancers noted how resonating really opened their awareness as dancers, and opened the space in a new way. I also played music that I had made the night before, which I thought would help with the idea of stretching time. The result for me was almost like watching zombies. The resonating was incredibly primal, and as a result, was bit difficult to watch. The music became a little scary sounding, and became more “spacey” than anything. I also played some ambient sounds of footsteps that got a little creepy as well. So, we did the structure again, and I gave them a musical phrase over which to resonate. I improvised on my guitar with some gentle affects on it, and over all, the piece got prettier. It became something I can imagine making, and wanting to share. There were some incredibly touching moments, some really beautiful things to watch, all due to assigning a melody to this idea of resonating. It was beautiful to see how a simple compositional idea could affect this dance piece.

The music being played live gave the performers something of a different awareness as well. They felt like they had the freedom to play with it, rather than it being a constant in the equation. I found this funny, because I could have easily recorded what I had improvised and played it. It was the knowledge that the music as being created in that moment that changed their perception of it.

My goal through this fellowship is to develop a process with which to approach collaboration with choreographers. This past weekend, I learned a tremendous amount about how dances are made (or at least one kind of dance). My goal as a composer is to create a score that can exist only for that piece. When De Facto and I discussed certain moments in our set structure that worked better than others, I asked them how they would then repeat those moments. Kelly spoke to emotional arcs getting repeated, not necessarily trying to land in certain physical moments. She said that every piece of hers is an improvisational structure that has an emotional “goal.” For example, one of her recent pieces was to “transcend the space.” I imagine this gave the dance an emotional quality that was palpable to the audience. This feels like my avenue into composing for this type of work. I can make music that tries to “transcend space” or “stretch time” or “pretties” something. The next time I work with a choreographer, I would love to discuss the emotional content of what we are setting out to create as an approach to discovering the perfect sonic environment for that movement. Overall, this is what I took away from this workshop the most. Its not what the piece is “about,” its about how it feels, and my role would be to figure out how to represent that sonically.