Mining the Mine of the Mind for Minderals

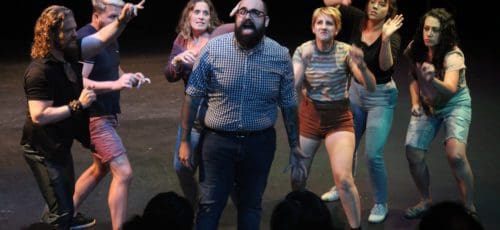

“Dualism has proved so popular because it feels right,” says “Mason Rosenthal,” played by Mason Rosenthal in Mining the Mine of the Mind for Minderals, a collaboration between Mason and Megan Mazarick that continues its run with two shows tonight and two more tomorrow, at 7:00 and 10:00 pm.

“Dualism has proved so popular because it feels right,” says “Mason Rosenthal,” played by Mason Rosenthal in Mining the Mine of the Mind for Minderals, a collaboration between Mason and Megan Mazarick that continues its run with two shows tonight and two more tomorrow, at 7:00 and 10:00 pm.

Talking with Megan and Mason about the show before it went up, I realized that if I had to call it something, I suppose I’d say it’s a theatrical installation. Moving the audience into differently designed spaces throughout the Jolie Laide gallery space, the design of the show echoes its content, examining the big question of the separation between body and mind, between form and consciousness, as attendees themselves move through a science-lecture-cum-movement-piece.

Minderals is firmly planted on the theater side of dance theater, but also has much of the physicality that you’d expect from Megan, who works primarily as a dancer and choreographer (but often with text-driven work), and Mason, through his 2011 training at the Headlong Performance Institute, where he also worked as an instructor.

“I saw his final performance at HPI,” Megan says, “and wanted to scoop him up before the theater people got to him.” Mason had moved to Philadelphia last fall to attend HPI, and Megan, seeing an aesthetically sympathetic figure, struck fast.

After the jump: diving into consciousness, science as backdrop, and Eckhart Tolle.

So, why investigate consciousness?

So, why investigate consciousness?

“As a performer I’m really interested in performance training, contemplative practices, and meditation, which led me to reading about the science of consciousness. I’ve been reading a lot about mirror neurons,” Mason says, which fire not just when you perform an action, but also when you see another person perform it. This could be another possibility for how we understand the creation of empathy, according to Mason.

“Actors were talking about being present or being in the moment, and becoming more accepting of this. Meditation has some kind of active benefit. A live presence is different from film and recording,” Mason says.

“I like the idea of working with science as a backdrop for making dance, and I liked that Mason had done this obsessive research on this one subject. This is research expressed through movement,” Megan says.

Mason particularly likes Eckhart Tolle, and his spiritual lectures. “He has a funny performance persona,” he says. “I’m also reading lots by [neuroscientist] Antonio Damasio. Scientists don’t know how to explain consciousness, but Damasio tries to describe what happens in the brain with emotions. His version of consciousness and Eckhart’s version come together.”

“I was very interested in how dorked out Mason was in all this stuff,” Megan says. “Mason spends a lot of time reading and watching things. I’m interested in what you’re bringing into the space. It’s the difference between thinking as an actor/director and as a choreographer. Working as a choreographer, it tends to be: ‘let’s make this awesome shit out of what we have here.’ I think I understand a lot of these questions on a physical level.”

“I’ve always liked the way theater artists take a lot of different things. Something good about working with Mason has been to alter my process. I’m willing to make up all the facts, but Mason is like no: he needs the facts,” Megan says.

But facts still must be processed, and thought experiments about consciousness and feeling put pressure on scientists who are struggling to understand, well, the basics of how our minds work. Take, for example, what’s called the “philosophical zombie.”

“It’s a thought experiment,” Mason says. “Could there be a version of you, but one that doesn’t experience any feelings? And the transporter experiment: if a machine could copy you successfully, destroy you, recreate you exactly elsewhere, is it you? Is there a soul? This leads into Eckhart-territory. Every moment you are dying, it’s just a serious of nows, not a soul that travels.”

They ask me if I’d do it, and I hedge, pleading responsibility for a newborn, although I’m curious about it. Mason and Megan both say they would. “I want to see what would happen,” Megan says.

They ask me if I’d do it, and I hedge, pleading responsibility for a newborn, although I’m curious about it. Mason and Megan both say they would. “I want to see what would happen,” Megan says.

“The extreme monist position is that it’s always a copy of you,” says Mason, as you move from moment to moment. Opposing dualism, which posits a separate mind and body, soul and flesh, monism says that there’s fundamentally only one substance. The Greek philosophers believed in a fundamental building-block; Leibniz discussed monads. Today, say Mason and Megan, we’d think of it as matter—and that all can be understood materially, including consciousness.

“The piece in the end asks the question of whether there’s an essential you,” Mason says. And this question pushes into the basic premises of performance as well.

“How do I bring authenticity, vulnerability, and realness to the stage?” asks Mason. “And is there such a thing?”

You can see how close they get in Mining the Mine of the Mind for Minderals, which runs tonight and tomorrow at the Jolie Laide gallery, 224 N. Juniper Street, Center City. Shows at both 7:00 and 10:00 pm each night, $18.