On “Available Light”

Alisa Regas: I’d like you to describe some of the history of Available Light and what the work is.

Lucinda Childs: In 1983 I choreographed Available Light, a 55-minute work with music by John Adams, décor by the architect Frank Gehry, and costumes by Ronaldus Shamask. And this was commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, in particular by Julie Lazar, who came to BAM [Brooklyn Academy of Music] in 1979 and saw Dance, my first major collaboration after working on Einstein on the Beach in 1976 with Robert Wilson and Philip Glass. In any case, once she saw Dance, which had a film décor by Sol LeWitt, and music by Philip Glass, she had the idea to commission a work for the west coast, and we met, and she said to me, “Do you know John Adams, by any chance?” And I said, “Yes, I know John Adams,” I knew perfectly well who he was, and had some of his recordings, and she also mentioned Frank Gehry, another very famous person on the West Coast, and the idea of a possible collaboration between these artists, the three of us, together. I thought it was a marvelous idea, and I came out to MOCA to meet with them, and we sat and we talked about it. John was very interested in the idea of creating a work for a dance company, and we talked about the fact that dancers, my dancers in particular, are used to working with a certain kind of pulse, or a certain kind of rhythmical structure that we can follow, which is very much the case with the music of Philip Glass. He more or less abided by that with his music, which is completely different from Philip Glass, but there are some parts of the music, which actually don’t have a metrical base, but they’re very beautiful passages, so I learned to work with my company in a special way regarding the music. Frank Gehry said, “I really need to meet with you, I really need you to come back out again, we need to talk about this and figure out what we are going to do.” So I came back out to Los Angeles, to his wonderful office in LA, and I said, “I like the idea of something perhaps on another level, perhaps on the sides,” and he liked this idea very much and did some drawings and sketches and we finally decided that this split level would be a lovely idea for the piece.

After the jump: set, materials, site-specificity, and returning to past work.

Alisa Regas: Can you describe the set and the materials that he used?

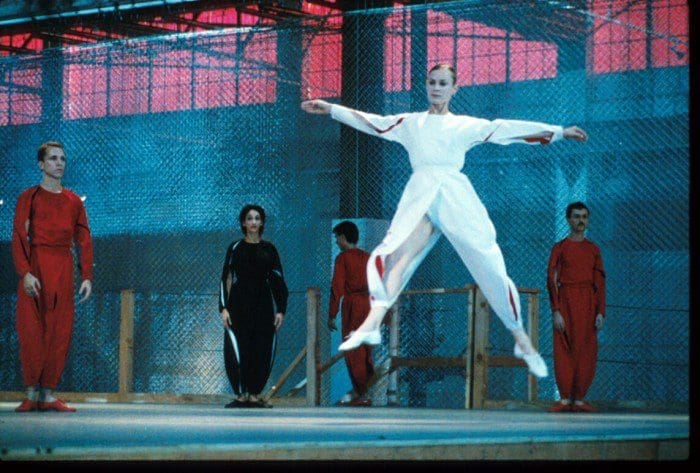

Lucinda Childs: What we decided also, at that time, Arata Isozaki had been awarded the commission for the new Museum of Contemporary Art, and Frank was invited to work on the interim exhibition space, so that space, which we went to see, is an abandoned warehouse where they repaired police cars. It’s a huge place with wonderful skylights, and we thought something that would work in this space with audience all around was primarily a wooden structure, a stage area on one level, and then the second level, the split level on another, which is 18 feet deep on one side and 22 feet deep on the other side, so not exactly a symmetrical shape for the upper level. But it’s made of wood, and he also used for the sake of lighting, which was done by Beverly Emmons, this chain link, which worked very, very well in this space. Beverly worked on beaming light through some of the skylight, and putting red gel on some of the skylight so that the light that came in reflected onto the chain link—it was a very beautiful effect.

I think Harvey Lichtenstein heard about the piece, and wanted to have it at BAM for the Next Wave festival, which I had already been in four years before, with Dance in 1979. This involved a complete re-adaptation because the proscenium space of the upper house is completely different from the Contemporary, so Frank came to New York and sat in the BAM opera house and said, “Well, we can do this or we can do that,” and he figured out a way to overlap the split-level set over the existing stage area, and it was rebuilt in such a way that it could work, and that was very exciting for me to feel “well, we really can do this and it really can be adapted to a traditional theatrical space” thanks to his willingness to do that and to take the time to work with us to make that possible. Initially, when Harvey said that he wanted the piece at BAM I didn’t think it would be possible, so I was very, very happy about that.

Alisa Regas: Can you talk about the site-specific nature of Available Light and how it’s adaptable to different spaces?

Lucinda Childs: Available Light—the title comes from the warehouse, the Contemporary, just the look of that space and the fact that we could beam in extra theatrical lighting from outside into the inside, which was a very special effect, which I liked very much. And, I guess to some extent that’s site-specific because that’s where we were and that’s what we did because of the space. And then the adaptation to BAM for Available Light was really quite a challenge, but I don’t think in any way it diminished the piece. I mean, the choreography could coexist exactly in the same way with the different levels because the different levels involved dancers on one level picking up on dancers on another level and that kind of counterpoint, which extends and reflects not only in the music but also in the space. For me, site specific is something that goes way back to my street dance in 1964, but we didn’t use that term at that time. That’s sort of a term that’s come about because of these kind of collaborations, I don’t think that term necessarily existed even at that time.

Alisa Regas: Could you speak a little more about Frank Gehry, specifically? How meaningful it is for you to be working with him again after so many years?

Lucinda Childs: Well one of the things, that even goes back to dance, is the generosity of some of these visual artists that I’ve had the opportunity to collaborate with. I never knew how many weeks that [Sol LeWitt] spent editing our film [for Dance], and the same with Frank—just incredible generosity, willingness to make it work, make sure it’s what I want, not just saying, “This is a Frank Gehry idea, and here it is.” It was really just wanting to interact with me, and wanting to see my dancers and wanting to see me dancing. He came to the studio to watch us. I think that after so many years, a situation like that and a collaboration like that, you develop a kind of very special friendship, that even after so much time, I feel like—we went out there to have lunch and it took us not much time to catch up. It feels like a friend, in a wonderful way, and it comes from this collaborative work, the kind of generosity and willingness for everybody—because of course we want the production to be the thing that works, so everybody is working in that direction. You can’t work against each other; you have to find a way to share the ideas to make the production work.

Alisa Regas: Moving on to John Adams, you’ve worked a lot with him over the years. Could you talk about the relationship that’s evolved with him as a collaborator?

Lucinda Childs: John’s music had already been published and was already available in the 1980s. I think he had already been to New York by then, with performances, and Available Light is more or less in an earlier period, it has some semi-abstract qualities, almost an emotional quality, so it’s very, very different from Philip [Glass], and very interesting, because it’s still in a minimalist category, but so different from Philip Glass. The company did a work in progress version of the piece in France before the set was built, and he came and watched the dancers. I had dealt with some sections where the dancers could easily get lost because there was no metrical structure for them to follow, but they developed a sense of timing, so they were able to very precisely start at a certain place in the music and end the choreography in a certain place in the music, without any kind of pulse to guide them. That worked very well, it was actually a challenge that worked very well. But the other part of it was that John said, when the dancers are jumping, there’s a sound. I said, I’m not able to really do anything about that, I mean, that’s just dancers. We laughed about it later because he went on to work with Peter Martins at City Ballet when the dancers are on pointe; those shoes make a lot of noise.

In any case, we joked about it later on, and I’ve had the opportunity to work with his music since then. I’ve worked with Chairman Dances from Nixon in China who have done a piece for Monte Carlo ballet with his music, which is one of my favorite and one of my more successful pieces, I would say, because it’s been performed by other companies, and also recently working on Doctor Atomic. I had also the opportunity to direct and choreograph it in Strasbourg recently. Even though I knew the opera and had worked on the premiere with Peter Sellers as a choreographer, I feel there’s always something there in the music that you can listen to again and again and again. And, it feels like a real treat to have that opportunity.

Alisa Regas: How is Available Light structured?

Lucinda Childs: It’s a piece for eleven dancers. Eight dancers normally occupy the stage level, which is the lower level, and three on the upper level works for me as a perfect balance between the upper level, which is smaller, and the lower level. The piece is structured very much based on the structure of the music. It’s almost an intuitive process of how the structure for the choreography evolves: it really depends on what the music sounds like. But for the most part, what happens during the piece is dancers are in three different colors—black, and red, and white—and throughout the piece there’s an exchange of the dancers from the upper level to the bottom level, and so you’re always seeing a different arrangement, with the colors especially, to highlight the interactions of the dancers between the two levels and different dancers on different levels at different times.

Alisa Regas: How is it meaningful to you to revisit this piece so many years later and also to set up your new company?

Lucinda Childs: I’ve been fortunate since the revival of Dance, which was almost five years ago, to have the same group of dancers with me now that were with me in 2009 when we revived Dance, and also, to have gone through the process with Einstein on the Beach of reviving the field dancers for Einstein with this new company. I made certain adaptations for them, particularly with this group in mind, because if I had a completely new group of dancers I don’t think I could have done quite what I managed to do with this revision of the “Field Dances.” That will happen with Available Light: there’s some material that would be exactly the same, but I will probably have the chance to rework some of the sections with this company, with this group of dancers. It means a lot that they’ve worked with me for so many years and they understand how I work with music.

Alisa Regas: What license does this company give you to do in your choreography?

Lucinda Childs: What we find is that even if a new dancer comes into the group, they pick it up so quickly because there’s something that exists there in the company, a sort of an understanding, and that was not the case five years ago, it was really like having to teach absolutely every single one and working at a certain pace, so that you can’t move ahead unless everyone is on the same page. Right now, we can rush through material in a completely different way, without my worrying if everyone is catching on, to cope with the enormous demands that I make, in terms of memory and stamina and so forth.

Alisa Regas: Could you speak to bringing this work to a contemporary audience and a whole new generation of dance fans, and viewers, and architecture fans?

Lucinda Childs: I’ve been in a situation where, working with Robert Wilson and working with my company, that these are for me two different disciplines, in a way. What’s wonderful about Einstein is that the dancers have the opportunity to participate as performers, but my choreography is something quite separate, in terms of the orientation it’s almost one-hundred percent abstract. I’ve always worked like this and I think there’s been an interest in the discipline involved in this kind of work and more demand to see earlier works, the works where there was no music at all. And to appreciate how demanding these works are, because I think that there’s been a tendency for some of the younger generations to move in the direction of Pina Bausch without being like Pina Bausch but very much in a theatricalization of dance. Now, I think that’s reached a certain evolution and people are wanting to come back to some of these very basic ideas, and this more strict discipline that’s involved, and I find that people are really appreciating this and even just recently reviving a Gavin Briars piece in London, not an easy piece at all for dancers to learn, but the public seems to have an appreciation for this kind of work at this particular time.

Alisa Regas: What are the basic ideas that you are working with in Available Light for choreography?

Lucinda Childs: Well everything in the space is important. There’s no fixed focus. There will be some solo moments, but for me it’s about space, it’s about time, it’s about interaction with the music—people will have different reactions as to what they get from it. For me, it’s just a satisfying experience to say, okay, the dancing is the dancing and is in and of itself, important as an art form, and I want that to be basically where we’re coming from. There’s no agenda, it just is what it is, and I think Merce was probably the one who spoke most strongly for that, that the dancing in and of itself is important, and what we strive to protect.

Alisa Regas: What are you thinking about when you’re constructing the piece that has nothing to do with the music?

Lucinda Childs: That comes from watching the Cunningham dancers, who are trained in two-second intervals. Merce trained them to count in two second intervals, and there’s no music at all, and so they sometimes didn’t even hear the music of John Cage and David Tudor until the performance, but when I was watching rehearsals, it’s just so beautiful to see the dancers working like this, and keeping a common pulse between them, and I thought this was a fascinating thing to explore in the 1970s with my dancers, so I didn’t use any music at all until I met Philip Glass.

Alisa Regas: Where do you think your work has gone since Available Light? And how do you see the trajectory of your career?

Lucinda Childs: I think that there are distinct stages of the Judson period, which is influenced by the Cunningham and Cage period and then all of us moved in different directions to the postmodern world, minimal world, then I think that the next step in a way was becoming involved with Einstein on the Beach, and moving back into the traditional spaces with works, admiring so much what he did and what he’s accomplished. Also, working in opera for the past twenty years. I find that I never would have accepted some of these commissions, but now I feel that it’s something I can get involved with and bring my sensibility to it, and I’m not the kind of director or choreographer that thinks there’s something wrong with these operas, it’s just the opposite. I think that they’re terrific and should be supported, and one should be loyal to them, and bring them to life. That’s what’s been exciting for me now, not to put them in a different setting with all kinds of other agendas that don’t have anything to do with the opera. I like to deal with the opera itself, and what’s there.

Alisa Regas: Is there anything you’d like to say your company?

Lucinda Childs: Well, it’s our third major project together and it looks like I’m going to keep the group together for the most part, and that’s really exciting for me. I think it’s the only time in the history of the companies I’ve had since 1983 that I’ve had a group for so long, together. It really means a lot.

Alisa Regas: This has been a rebirth of your career in America: what does that feel like?

Lucinda Childs: Since the revival of Dance, which was an opportunity for me, because they were able to deal with the digital transfer of the film, which made the work sort of immortal—we could take it anywhere and it could last as long as we like—that has put me back on the map for a while, because in the year 2000, which was my last season with the company, it was almost nine years before I started up again with this new project and this new company. I primarily worked freelance in Europe, and that suits me, because I don’t have the patience to stay put, and try to fundraise. I like to stay active and keep working at what I’m trained to do, in different kinds of projects. So, when the phone rings and someone wants me to do a project in Europe, chances are I’ll jump on a plane and go.

Alisa Regas: Can you speak about Pomegranate and what the relationship has been like over years?

Lucinda Childs: In the year 2000, when I had my 25th anniversary season at BAM, which went very well, I have no regrets, but it was a struggle, because of difficulty with the national endowment and difficulty with fundraising in New York, and that’s partly why I more or less disbanded the company. It was a tremendous amount of pressure on me personally, to protect my board of directors from disaster, to be diligent in how everything was organized so we didn’t end up with some huge problem, which could easily happen, and Pomegranate is just fantastic for me to feel like I’m basically dealing with my dancers, and a huge responsibility has been lifted from me in having an administrative backup. Pomegranate has been more than an agent, they’ve really been a producer, involved in figuring out how to make these pieces have a life, and where they could go, and where they could be seen, and it’s been wonderful for my company. When I went to Linda, because of the possibility of Einstein, I said, Dance is coming along, and the people at Bard want to know “who is your administrator?” I didn’t even have any dancers, so we did a big audition to make it possible. It’s been really the best period for me, to have this kind of relationship with Pomegranate.