In “Urgent Care,” The Colored Girls Museum Offers Itself as a Sanctuary and First Responder

Walking down Newhall Street in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, it’s hard to tell that one of these houses is not like the others. After a moment, you’ll find a wooden sign for The Colored Girls Museum (TCGM) outside of a 128-year-old Victorian twin. Since 2015, TCGM has been quietly redefining the role of museums in Philadelphia. The house is the home of the founder and executive director of the museum, Vashti Dubois. She founded the museum as a celebration of women of color, as well as a living memoir and sanctuary. Michael Clemmons is the curator for the museum, and has known and worked with Vashti for many years. “I think that what our museum does is very unique, distinct from everything else that’s out there,” he says. “In many ways, it’s the only museum of its kind.” From July 29 to July 30, the museum will be presenting its last showings of the current show, Urgent Care: A Good Night’s Sleep, before closing to prepare for its Fringe Festival event, Urgent Care: A Social Care Experience.

TCGM is telling a story that few other art spaces are, in a way that uses art as a place for conversation. The museum is a living monument “for the ordinary and extraordinary colored girl,” bringing her voice out highlighting her concerns. “When you shine the light on anything,” says Vashti, “you begin to notice its extraordinary qualities, but you have to look at it first.” The museum’s exhibitions respond to current social issues, and the “Urgent Care” shows reflect heightened concerns for women of color after the 2016 election. There is a huge variety of beautiful and fascinating objects throughout the house, which are a conglomeration of historical artifacts and new works of art. Artists who work with the museum either submit their own work, curate a space, or add objects from their own past or family history that are significant to the space’s collective memoir. “Those objects have a story that is important to the woman submitting them,” says Michael, “which is curated into the space.” The museum leaders and staff refer to the museum with she/her pronouns, speaking of the space as a person, rather than a stagnant building. Vashti explains how this reflects the moving and changing aspects of the museum: objects come and go, and rooms within her walls change to reflect changing times. “The concept in a way is very simple,” says Michael. “In a sense, it’s a story that hasn’t been told, and it should be told. It’s very much a home, it’s relaxing, and it’s a different kind of museum experience.”

Walking into Salon 1, on the first floor, the museum already feels entirely different from any other galleries. Rather than white walls and echoing hallways, this is a home. Salon 1 is a part of the semi-permanent collection, and many works of art were a part of the inaugural exhibition in 2015. The paintings on the wall are hung in a “salon style,” covering the space, and are interspersed with small statues, old portrait photographs, and personal artifacts, including a singular knee-high tie-dye boot. There are very few name cards on the walls— instead, everyone who comes into the museum is brought on a tour. Through conversation, guests learn which paintings on the wall are by Barbara Bullock, a celebrated African American artist in Germantown that Michael described as almost a “mother figure” in the Philadelphia arts community. There are quilts from fiber artist Toni Kersey, and doll figures by Lorrie Patrice Payne. The experience is intimate and allows for conversations about the art — often, with the artists themselves.

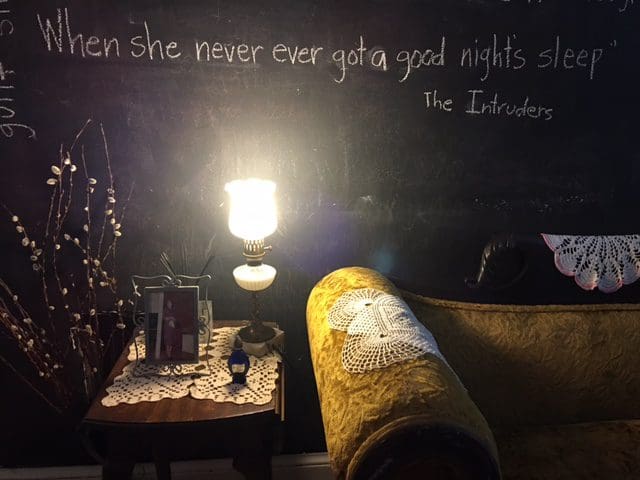

Upstairs, in the “Washerwoman” exhibit, artists Denys Davis and Monna Morton are often available to talk about the items of the room, which come from their own family archives. The room is a tribute to the grandmothers of the two women, who were domestic workers. “The installation was to honor the women with that kind of work,” says Michael, “particularly following the end of enslavement, when sometimes that was the only kind of job that could be had.” There’s a clothesline hung with linens, an antique iron, and a jar of bills that represent the immense savings that these women worked to put aside for education funds and community projects. This powerful exhibition was the first part of the permanent collection, although changes exist here, to. The words on the chalkboard wall been re-written to reflect the theme of “A Good Night’s Sleep:” one phrase says “All shuteye ain’t sleep,” and there are quotes from African American poets and novelists from passages about the difficulties of sleep. Words around the perimeter of the wall reflect “outside stressors,” the many worries that have been keeping African American women from getting a good night’s sleep for hundreds of years.

From the Washerwoman Room, or “Historical Record” in “Urgent Care;” photo courtesy of The Colored Girls Museum

While doing research for the curation of the exhibit, Michael found that “there is a lot of data about sleep disparity between the African American community and the mainstream communities. In the African American community, we are always aware of these different ailments where there’s a higher impact. So, you wonder how much of it can be related to something as simple as not getting a good night’s sleep.” Vashti had the original idea for the exhibit, first shown earlier in 2016. She had recently lost her husband, and began experiencing insomnia herself. She started thinking about how to use art to investigate the difficulty of getting a good night’s sleep as an African American woman. “We asked the question, how does the colored girl get a good night’s sleep, after 400 years of restlessness?” says Michael. To respond to that question, the museum began designing the exhibit around the elements that need to be in place in order to settle down to sleep. Some of these are remedies (the “Apothecary” downstairs is filled with such objects such as empty Benadryl capsules, lavender, and artistic renderings of medicines; one artist even submitted a bottle of Jack Daniel’s). Sometimes the spaces were filled with fragrances, music, and video projections that evoke sleep. “We’re losing sleep over the future of health care,” says Vashti. “We’re losing sleep over the future of education. We’re losing sleep over the future of our children, the safety of our streets, of our institutions, what will happen to the arts in our country. We’re losing sleep over lost girls, and lost boys.”

After the 2016 election, the Vashti and Michael decided to update the exhibit to include the theme of “Urgent Care” for the second half of “A Good Night’s Sleep.” “A lot of folks are definitely still in a period where they believe the colored girl is still in need of urgent care,” says Michael. “So, what does that look like as a first responder?” The museum has made itself into this “first responder,” a sanctuary and healing place for those in need. The first room is now “Reception.” The third floor includes “Triage” and a “Recovery Suite.” The Washerwoman Room is now a place for “Family Historical Record,” and the kitchen near the Apothecary is the “Aftercare” area. The house looks nothing, however, like a hospital ward, and that’s a good thing. The goal is not to look like a traditional medical center, but to search for answers in a different kind of remedy. “How can we respond to really crucial and urgent issues, particularly with the arts, in a way that can be healing, in a way that can offer solace, but also, a response?” On the third floor, an installation by Intisar Hamilton titled “Riverbed” places the theme of sleep in nature, in a mural that covers the walls and cabinetry of the room. Her mural questions why sleeping figures in art are almost universally white, and subverts the trend by placing the mural in the bedroom of a woman of color. At the same time, the mural is a calming landscape of rolling waves and stars. Across the hall, artists Joy Ude and Petra Floyd have created “Chamber,” a canopy of fabric that surrounds two basket-like seats. The space is hung with translucent envelopes, where anyone who identifies as a women of color can store a note on their concerns for the present day and hopes for the future.

Spaces like “Chamber” offer healing through contemplative resting. The coming exhibition will delve even further into the idea of using art as “Urgent Care,” with the next installment comprising of a “Social Care Experience.” The museum is a place “where you can grieve or cry, and then get up and say, what do we need to do next in order to improve or sustain ourselves?” says Michael. They are using the arts to provide that space, which will act as a place for conversation and a response to the current political climate. “I think that’s the direction that the museum is moving towards.” Right now, the museum is in the process of gathering artists who will be submitting their work or curating spaces. “To me it’s really exciting, because it’s at the point where the show is starting to form. We have a number of new artists that we’re really excited about.”

The show will have debuting work of many mediums, including various visual arts, film, and performance art. Destiny Palmer is one such new artist who is contributing to the upcoming exhibition, is a recent graduate of the Tyler School of Art, and creates intensely complicated and colorful paintings as well as fabric pieces. Lavett Ballard is bringing in her sculptures that incorporate synthetic hair. Lynda Grace is contributing new fiber art, and artists Nichole Shante, Calli Roche, and Shreya Pokharel are bringing their work “Communion” from Brooklyn, a piece about radical platonic love during times of struggle. New artists also include fiber artist Nastassja Swift and poet Magda Martinez. Other contributing artists have been there since the beginning: painter Barbara Bullock and fiber artist Toni Kersey are two of these “inaugural artists.” Michael notes that the artists that give submit their work are phenomenal in their support of the museum’s mission. “We have structured talks, but it’s really exciting to have four or five artists who just show up, and they can talk to the folks who are going through the museum. I’ve never experienced that, and I think it’s exceptional. In a sense, to us, it’s a kind of affirmation of what we’re doing.” He describes the submission process as entirely different from that of a traditional gallery. Artists view the museum as a community project that they become a part of. “Artists come, drop off their work, but then look around and say, ‘How can I help?’”

Like many artists, the contributors to the museum have entirely separate day jobs, and work long hours in order to produce their art. Celestine Wilson Hughes is a bus driver by day, and a creator of stained glass sculptures by night. Her three-dimensional, sparkling structures hang around the museum. Her work is so masterful, it’s hard to believe that she only began making art at 49. Michael himself has a separate day job, as the associate director of Workforce Development in the Temple University’s Center for Social Policy and Community Development. The center conducts community engagement, with projects such as adult education, and transition for youth from high school to further education. Michael is a Philadelphia native, and began his arts education at the Overbook High School. When he attended the magnet school, there was a flourishing arts program. He was always interested in the arts, and began to learn how to draw and paint. Michael, along with many other graduates of the program, moved on to go to an arts college. He attended the Philadelphia College of Art, now the University of the Arts, where he studied drawing, painting, and arts education. Today, he sees his roles at Temple and TCGM as distinct, but that his work is somewhat synchronized. “I find that the conceptualization and creativity is transferable.” His works, many of which are placed around the museum, center themes of social justice. “Four Girls from Birmingham” hangs on the wall of Salon 1. The work is comprised of four vessel figures made of ceramic, and four fans above them, two with West African symbols, as a tribute to the girls who died in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing.

As an artist and a curator, Michael has begun to notice trends that pop up in the artwork and artifacts around the museum. There are many ladders, for instance, which are a West African symbol, and often appear in his work as well. The museum features a surprising amount of fiber artists, with many different applications. Some, like Toni Kersey and Dindga McCannon, create intricate quilts. Joy Ude, who also works at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, created the “Mission in Print” series, which are embroidered pieces that line the wall of the Apothecary suite, and “Omission in Print,” a hand-stitched book with similar embroidery. These intricate works are quilted memoirs, and have family history photographs sewn into them. The museum has many dolls, some which incorporated artifacts themselves. A doll in the first room has a skirt made of old hymnal pages that the artist saved from being thrown away. One, in the “Recovery Suite,” is a model of a “topsy-turvey doll,” which were dolls that mothers made for their children during enslavement, when children weren’t allowed to play with dolls that weren’t white. The doll could be turned around as soon as the children were out of sight of the overseer, and the skirts would hide the “white doll,” revealing beneath the skirts a doll that looked like them in a beautiful dress. There are many portraits throughout the museum as well, from Joy Ude’s embroidered photos, to photos of Monna and Denys’ grandmothers in the “Washerwoman” room.

There have been a number of collaborations between TCGM and other arts organizations. “Graduation Night” was an installation by various artists that was also a part of the exhibition “i found god in myself,” at the African American Museum in Philadelphia. Michael would like to see more collaborations like these between different institutions, and broader interconnectedness between groups. “People tend to view the arts scene as homogeneous, while in fact, there are many distinct communities within that community.” He would like to see more museums of this kind around Philadelphia and in other cities in the country. Women of color make up much of the audience, but their patronage is made up of people of all races, and not just women. The museum attracts many as something that is entirely unique: impacts from the outside climate advance the dialogue inside the museum, which is ever changing and shifting. As a welcoming and warm home, it is a space that may allay fears, but also, act as a call to action. Vashti has been known to say that “The Colored Girls Museum is a sanctuary not for Colored Girls Only, but for anyone who is ready for a conscious revolution.”

Urgent Care: A Social Care Experience

The Colored Girls Museum

$15 / 60 minutes

The Colored Girls Museum

4613 Newhall Street

Sept 8 at 7pm + 8pm

Sept 9 at 7pm + 8pm

Sept 15 at 7pm + 8pm

Sept 16 at 6pm + 7pm

Sept 22 at 7pm + 8pm

Sept 23 at 6pm + 7pm

The exhibit will end on October 31, 2017.

— Isabella Siegel

Photos: Jere Paolini (Chamber), Gaciru Matathia (Communion), Isabella Siegel (Recovery Room, first photo of Family Historical Record, and “Four Girls from Birmingham” by Michael Clemmons)