Dada Down South: Barry Rowell talks about his play Floydada

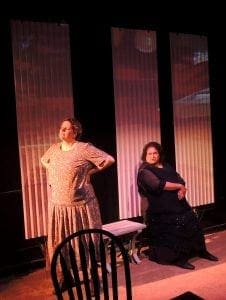

How do you combine dusty plains, small towns, and pre-surrealism reactionary art? In Barry Rowell’s Floydada, theater, music, and puppet projection present two sisters, one a prodigal artist who has gained fame in the big cities, the other stationary in the town for years and years. The homecoming sister brings Dada art along with her, and the two scheme to present a Dada cabaret for their small town.

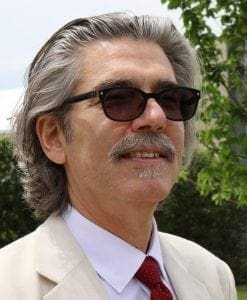

Barry Rowell hails from Fort Worth, Texas, and is now the playwright and co-founder of Peculiar Works in New York City. The Obie-award winning group has been producing interdisciplinary and engaging art since 1993. The work is avant-garde in a way that mirrors the post World War I Dada movement. Dada art, poetry, and cabarets were collages of strange, mis-matching objects and images, from toys to toilets. Floydada does the same, bringing together revolutionary anti-art, a host of different disciplines (including Leila Ghaznavi’s whimsical puppet projections), and small town Americana. Barry has been writing plays for decades, and loves to bring together seemingly-disparate elements into one, cohesive work. We were able to chat with him about his origins as an artist, and the strange, wonderful world of Floydada.

FringeArts: Where are you from, and how did you first get involved in the arts?

Barry Rowell: I grew up in Fort Worth, TX, but I was born in Odessa — which is what most people picture when they think Texas: flat, dusty plains with oil pump jacks as far as the eye can see. I saw my first play, Through the Looking Glass, at Odessa College’s replica of Shakespeare’s Globe and I was hooked. My dad had done theater at Odessa College — my grandmother said that she cried and cried when he died as Lenny in Of Mice and Men “because he was just so stupid.” There were several theaters in Fort Worth when I was growing up: we saw Casa Mañana Summer Musicals, Shakespeare in the Park (you sat on a hillside and the stage was built out of an old WPA-era picnic building), and my mother worked at Texas Christian University so I got to see all of the theater department productions there. I made my professional acting debut at Fort Worth’s Stage West while I was in college. It’s always been a very strong arts community.

FringeArts: Who are some artists that you look up to?

Barry Rowell: I’m blown away by (and a little envious of) artists whose work is intensely physical: Pig Iron, of course, Elevator Repair Service, Yanira Castro (whom Peculiar Works has produced a few times—and she’s as wonderful to work with as her work is to watch), Nicole Canuso, Geoff Sobelle, The Bang Group. I’ve had the good fortune to work with Lake Simons, a gifted performer and object theater/puppet artist here in NYC (and Fort Worth, too). My friend Howard Fishman is both a fantastic singer/songwriter and a talented theater artist—his piece about The Donner Party, We Are Destroyed, is hauntingly beautiful. We saw James Thierrée perform two years ago (he’s a choreographer and Charlie Chaplin’s grandson) and he’s amazing: it was some of the most remarkable physical performance I’ve ever seen. I wish I could write poetic plays as Ruth Margraff and Mac Wellman do. And we’ve been seeing shows in the Fringe here in Philadelphia for years and those have been some of my favorite shows ever: Bruce Walsh’s Chomsky vs Buckley 1969; New Paradise Laboratories’ Rrose Selavy Takes a Lover in Philadelphia; Across by Mark Lord, Anti-Salon (Antigone in a beauty salon)…I could go on and on.

FringeArts: When did you start writing plays?

Barry Rowell: My bachelor’s degree is from TCU and I did a year of graduate work at the University of Texas in Austin where I studied acting but I took as many history and criticism classes with Oscar Brockett as I could—he influenced the work I do now more than any other professor I had.

I started writing plays because I was producing a second stage series at a long-gone Off-Off Broadway company and the playwright who was supposed to write our debut show dropped out at the last minute. The artistic director said I’d have to cancel and I said, “Like hell I will.” So I made an adaptation of Dracula that combined texts from the novel, a medical textbook, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s On Death and Dying, and some of my original writing into an abstract collage piece set in a hospital in which the vampire (who never appears) symbolizes the characters’ fears of death. A year later, I went back and rewrote it (the first draft took me about 2 weeks—it was very rough!) and Before I Wake became the inaugural production of Peculiar Works Project in 1993.

FringeArts: What’s your day job?

Barry Rowell: I have had many jobs over the years. At my first NYC office job in 1987, they had a PC but it wasn’t plugged in because no one knew how to use it. I got a book and taught myself WordPerfect. Gradually, I learned more and more software over the years so that my day job now is freelance print production for advertising. I take someone else’s design and make sure that it will print properly when it goes to press. My primary clients are pharmaceutical companies: I create some packaging and ads but spend a LOT of time on the prescribing information. You know, that piece of paper you throw away without reading after you open the box with your medicine? It ain’t sexy but it supports my arts habit!

FringeArts: How was Peculiar Works formed?

Barry Rowell: Ralph Lewis, Catherine Porter and I formed Peculiar Works in 1993. We’d all worked on productions by En Garde Arts, a site-specific performance company here in NYC, and were interested in that work. We had an idea that not using theaters, in addition to being a lot more fun, might be cheaper (it often isn’t because you have to cart in or build all of the things that theaters already have: lighting, a grid, chairs and risers, dressing rooms, sound equipment, etc). With site-specific work, the unique sites impact our work, the work impacts the site, and audiences experience both in surprising new ways. Every show is an adventure: we have done shows in office buildings, the main post office in New York (one sorting room was two city blocks by itself), an old school building/community center, Judson Church in Greenwich Village, and our Obie award-winning tribute to the birth of Off Off Broadway led audiences through the streets of the West and East Village (in two parts—we had around 90 performers in each part and each route was a couple of miles!)

FringeArts: How did you come up with the idea for Floydada?

Barry Rowell: Floydada (Floy DAY duh) is a real town in west Texas near Lubbock. When I saw the sign for it, sometime in the early ‘90s, I told Catherine that I had to write a Dada play set there because it looked like Floy Dada. It took me several years to write: at one point, it was a radio play about the wife of a preacher who wants to escape the town but I couldn’t figure out how to get the Dada into it. The idea of two sisters came to me because I wanted to write something for Catherine and Nomi Tichman, two of my favorite actors. The conflict of a prodigal who has been forced to return home to her homebody sister made sense with that. What’s funny is that I learned that Dada really did eventually spread to odd little places — the catalogue for a Dada retrospective several years ago said that there was a Dada cabaret in Papua, New Guinea!

FringeArts: Why did you want to incorporate Dada art?

Barry Rowell: Both Dada and Texas originally came from the town name. Beyond that, there’s the tradition of “cowboy poets”: people who are creatively inspired by the wide-open skies and empty plains on which they live. I believe that everyone has an artistic impulse and most of them just need a catalyst to push them into exploring it. And I know people in small towns who are pretty tolerant of their neighbors, accepting, even indulging, their eccentricities. Perhaps creating a Dada cabaret in a town of 2,000 or so is pushing the bounds of that goodwill, but the sisters didn’t know that when they started…

FringeArts: What is working with Catherine Porter and Nomi Tichman like?

Barry Rowell: Catherine and I have been best friends since we met at TCU in 1984, she moved to NYC in 1990, and we got married in 1993—one month after PWP’s first production. I have never written a play that didn’t have a significant part for Catherine and I never will because no one interprets my work (or anyone else’s, for that matter) better than she does. As for Nomi, I have a photo over my desk of Catherine and Nomi in the first production of Before I Wake so we’ve all been working together since 1992 (and as actors before that). Not only is Nomi a wonderful actor but she has a beautiful singing voice, plays the piano (in this case a toy piano) exceptionally well, is a professional vocal coach, and a very dear friend. Floydada is dedicated to the two of them: they are Floydada.

FringeArts: Your show is very interdisciplinary — what are the challenges that come with this, and what does it enable you to do that you wouldn’t otherwise?

Barry Rowell: The biggest challenge is scheduling! Everyone is very busy and it’s hard to get them in the same room together (in fact, we’ve only done it a few times over two years of working on the piece.) What it enables us to do is create a richer experience. For instance, the sound effects are created live onstage by our stage manager, Heather Olmstead, and they’re a pastiche of real life, the distortions that one character experiences, and an aural reflection of the collage theme in our production. And the interdisciplinary aspect fits well with Dada: the performances at the Café Voltaire in Zürich had songs and skits and poetry recitations and homemade costumes and sets and puppets and films, all made by people who had trained to be visual artists and writers.

FringeArts: Have you worked with puppetry before?

Barry Rowell: Leila Ghaznavi came to us through our projection designer, Lianne Arnold. Lianne wanted the video to have a role in the production, not just be a backdrop or indicate location, and the whole team agreed. Much of the visual art of Dada was collage, so Lianne decided that she would create collages in her projections and she recommended bringing Leila in as projection puppeteer because they had worked together in a similar vein on another project. We all agreed that we wanted Leila to be visible to audience so she and our director, David Vining, worked that into the staging and the more we saw her in the piece, the more we wanted her to have a role. After the initial run here in NYC, as we began making the show more “portable” for touring, we have found ways to expand her role. Now, she’s a character who interacts with Ada and Dalia but is not seen by them; we refer to her as “The Muse.”

PWP has presented puppet artists in larger projects in the past and our production in the NYC post office, Manna-Hata, had a lot of object theater by Lake Simons. But we’ve only scratched the surface in that arena. I’m currently reworking Manna-Hata for another production in 2018-19 and I expect there will be a lot more object theater in that incarnation.

FringeArts: How do the projections work in the show?

Barry Rowell: All of the video is live feed with a camera station set up onstage for Leila to manipulate various materials in the collages. Lianne is such a gifted artist that I know it’s only a matter of time before she has too many big gigs to be able to do our productions (and I will be incredibly happy for her, if disappointed for us, when that happens). Her approach to projection design is very much about how her contributions help tell the story or highlight something in a particular moment. It’s a delicate balance between creating an appropriate environment and adding another layer to visual narrative, particularly since video can easily be distracting to an audience. Lianne suggested the particular scenes in which she wanted to use video—the first appearance is pretty subtle and then nothing gets added to it for almost 30 minutes—and David and I agreed with her entirely. Her idea to have Leila manipulate the images in view of the audience and to have her fingers seen in the projections is bold but we all agreed that it was the right choice: Floydada is about the process of creating so it’s fitting that this is reflected in the video.

FringeArts: Where does the music come from?

Barry Rowell: Seth came to see an early workshop of Floydada in an art gallery. After the show, he told me that he was from Odessa and that he wanted to write music for the play. We got to know each other’s work over a couple of years — he composed music for a Depression-era play we did in 2010, I went to hear his music in concerts by small orchestras and chamber ensembles—and we talked about how to approach the show. I had written several poems for the sisters to perform and Seth set them all to music. Sadly, most of the poems were very long and the music made them longer, so we then had to trim them down.

There are two ways that music is used in the show. First, songs that the sisters create and perform in their cabaret that are accompanied by Nomi on toy piano; these are fairly straightforward and usually fun or funny. Then there are the performances that function much as songs in a musical: what the audience hears is not literally what is happening but an amplification of life. They are accompanied by an electric organ (also in view of the audience—we don’t believe in hiding anything if we can at all help it).

Coincidentally, in our initial production, a family from Floydada was visiting New York and wrote me to get tickets for the “musical about Floydada.” I responded and made sure they knew that it was not a musical but a play with original music. They came anyway on opening night. I joke now that I know exactly what response the sisters got after their first performance in the play: the father was very polite, found several nice things to say about the show (“all of those towns and places are exactly where you said they were” was my favorite), but it was definitely not their cup of tea!

FringeArts: Why did you want to show at the Maas Building’s Fifth Side?

Barry Rowell: We fell in love with the Fifth Side the moment we walked in: the architecture is unique, the space is beautiful, there is outdoor space that we can incorporate into our production, and it has everything we need—no bringing in chairs or lights or other equipment! Plus, it’s going to be a discovery for many Philadelphians: a lot of people know it as a music and event space but I think they’re going to see what a great performance space it can be, too. Don’t expect your dad’s black box here!

FringeArts: How did you come to join this year’s Fringe Festival?

Barry Rowell: This is our first foray into performing in fringe festivals. Catherine and I started coming to the Philly Fringe in 2000 (could have been ’99…we’re not sure) and have wanted to bring something here ever since. One concern with many Fringe festivals is the shared venue: your show has to set up and strike in about 10 minutes and that’s at odds with the kind of environments we prefer to create, especially for Floydada. We got VERY lucky with The Fifth Side: we are the only show in here for the week. So the show everyone will see is the show our team intended: visually complicated and layered and tailored to fit the environment and architecture. We could not have asked for better partners on our first Philly Fringe show than Ben and Joanna at the Maas Building!

Floydada

Peculiar Works Project

$20 / 90 minutes

The MAAS Building 5th Side

320 North 5th Street

September 13 — 16 at 7:30 pm

— Isabella Siegel

Photos: Ellen Rowell (first photo), Peculiar Works Project (all other photos)