A House is Merely a Container

This is a guest post written by writer, editor, critic, and professor Stefanie Sobelle. She is also the dramaturg of HOME, the latest work from Geoff Sobelle. Her book The Architectural Novel is forthcoming from Oxford University Press, and her criticism has been published in Bookforum, the Financial Times, BOMB, Words Without Borders, Jacket2, and the Review of Contemporary Fiction.

What do we mean when we call a place “home”? Home might be the place where we live. It might also be, in game terms, the place we are trying to reach—the goal. We often associate with “home” concepts of comfort, safety, family. When we add an article, home can become more dire: they took her to “a home.” Home is not a house per se; a house is merely a container. It holds residents and furnishings, performances and privations. A house has identifiable limits—walls, doorways, staircases. A house can be discomfiting, sinister, cold, hostile, welcoming, familiar, secure. A house can be empty or full, dead or alive. A house can even be a dream.

We clean these houses to ward off chaos from the outside world; we remodel them and decorate them to bring them closer to our idea of who we want to be; we move into them and out of them; we buy them and we sell them; we take them and we lose them; we raise them and we raze them; we rent them and are rent from them. More often than not, these days at least, a house is often constructed by unknown contractors before we arrive, and destroyed by unpredictable forces after we leave, as if by magic. Its builders and demolishers are faceless and nameless. Its systems are complex and often mysterious.

We clean these houses to ward off chaos from the outside world; we remodel them and decorate them to bring them closer to our idea of who we want to be; we move into them and out of them; we buy them and we sell them; we take them and we lose them; we raise them and we raze them; we rent them and are rent from them. More often than not, these days at least, a house is often constructed by unknown contractors before we arrive, and destroyed by unpredictable forces after we leave, as if by magic. Its builders and demolishers are faceless and nameless. Its systems are complex and often mysterious.

We live in these houses alone and with others. Geoff and I each rent small Brooklyn apartments minutes from one another, small enclaves in larger houses populated by owners we call friends. But we grew up sharing spaces—bathrooms, backyards, garages, bunk bed hideaways, hillside forts, paper castles, bookstore attics, witchy ponds, and station wagon waybacks. We share so many memories of these childhood spaces—they tell us who we are and who we’ve been—and so we always feel a bit unsettled when we discover where those memories diverge.

I suppose we are all haunted by our memories of previous houses we have inhabited and of the traces left behind by those that came before us. In turn, we haunt those that come next, and this can be true whether the house takes the form of a single family dwelling, an apartment complex, a hotel, a bivouac, a congress, a prison, a theater. But home is less a material thing and more an idea, an experience, a feeling, an illusion. James Baldwin writes in his beautiful brief novel Giovanni’s Room that home can also be a person, or at least how we feel when we see or think of that person. “Perhaps home is not a place,” he writes, “but simply an irrevocable condition.”

I suppose we are all haunted by our memories of previous houses we have inhabited and of the traces left behind by those that came before us. In turn, we haunt those that come next, and this can be true whether the house takes the form of a single family dwelling, an apartment complex, a hotel, a bivouac, a congress, a prison, a theater. But home is less a material thing and more an idea, an experience, a feeling, an illusion. James Baldwin writes in his beautiful brief novel Giovanni’s Room that home can also be a person, or at least how we feel when we see or think of that person. “Perhaps home is not a place,” he writes, “but simply an irrevocable condition.”

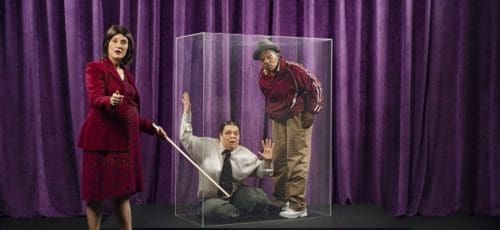

HOME explores this relationship between thing and idea, between place and feeling, between what we control and what occurs in spite of us. For so many people, home is either untenable or a marker of incalculable loss. As current news continues to relay devastating stories of mandatory removals—removals caused by violent exiles, deportations, floods, earthquakes, and fires—we are reminded of the fragility and endurance of this irrevocable condition that we call home.

Over the last two years of working on this project, Geoff and I have turned often to Richard McGuire’s graphic book Here, in which each spread features the same corner of an ordinary living room in an ordinary New Jersey house, set over millennia (long before and long after the house’s construction). Here raises important issues regarding the relationship between an individual life and the vastness of deep time. One of its key features is that each spread is captioned with a year—2014, for example—and then punctuated with boxes that open into other years, other centuries. McGuire’s dwellers make love, grow old, grow ill. New residents move in, not all human. As such, Here emphasizes the reiterations of living that occur within a house—the echoes of private lives with each other over time. We live with ghosts of the past and the future, McGuire suggests. We live with the mammals that we have displaced and the insects that remain. Domestic time transcends an individual’s lifespan entirely. As such, domestic time is not some rectilinear experience but rather an experiment in simultaneity and repetition, much like a dance—a tango, perhaps, with new dancers looping in and out of its choreography.

Over the last two years of working on this project, Geoff and I have turned often to Richard McGuire’s graphic book Here, in which each spread features the same corner of an ordinary living room in an ordinary New Jersey house, set over millennia (long before and long after the house’s construction). Here raises important issues regarding the relationship between an individual life and the vastness of deep time. One of its key features is that each spread is captioned with a year—2014, for example—and then punctuated with boxes that open into other years, other centuries. McGuire’s dwellers make love, grow old, grow ill. New residents move in, not all human. As such, Here emphasizes the reiterations of living that occur within a house—the echoes of private lives with each other over time. We live with ghosts of the past and the future, McGuire suggests. We live with the mammals that we have displaced and the insects that remain. Domestic time transcends an individual’s lifespan entirely. As such, domestic time is not some rectilinear experience but rather an experiment in simultaneity and repetition, much like a dance—a tango, perhaps, with new dancers looping in and out of its choreography.

This notion of such “replacement” in and out of time is in the foundation of HOME, both in terms of the work’s form and its content. Performers replace each other. Objects replace each other. Characters replace each other. We are always re-placing, finding place again. We turn our dwelling places into something new, through construction, restoration, and destruction. Places are always fleeting. We are, in a sense, all guests in the residences we inhabit. And whether through imperialism, gentrification, migration, aging, death, et al, we take the places of one another, another takes the places of us, and for better or worse, we re-place.

HOME accommodates these life cycles. It meditates on the ways that home is deeply private—full of pain and beauty and banality and magic—and also is produced publicly—an interaction of community, friends, family, strangers, and even powers that are beyond our control. In this way, home is an experience generated by collaboration. That aspect of home feels particularly acute these days. We can open the door. If we do, will we say welcome?

We invite you to join us in this house that is theater. We invite you to collaborate with us in creating, for a little while at least, a condition of home.

—Stefanie Sobelle

HOME

Geoff Sobelle

Prince Theater

1412 Chestnut Street

Sept 13-16

$35 (general)

$24.50 (member)

$15 (student + 25-and-under)

All photos by Maria Baranova.