There’s Nothing Called African Music: A Conversation with Olivier Tarpaga

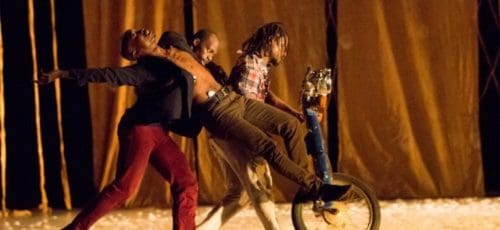

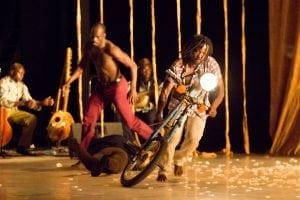

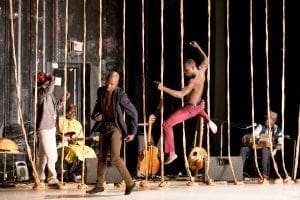

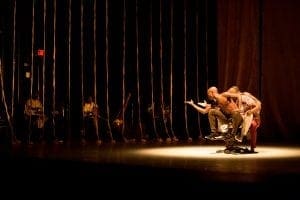

“Dance and music are one in our tradition, and they come in one body.” This is what Burkina Faso-born dancer, choreographer, musician, and composer Olivier Tarpaga offers when asked about the relationship between the two mediums in his latest show Declassified Memory Fragment. Positioned as an “open letter” to life in a few African nations that have experienced cultural and political tumult over the last several decades, the piece opens tonight and runs from Oct 12-14 here at FringeArts. As the dancers move throughout the performance space, a group of virtuosic musicians play from the sidelines, informing the dancers’ movements and energies. “Live music affects everything and the dancers feel different and create different when the music is live,” Tarpaga asserted in a previous interview. Live music has always been a hallmark of Baker + Tarpaga Dance Project, likely because music has always been a hallmark of Tarpaga’s life.

Growing up in Burkina Faso, Tarpaga didn’t have to look far to find great music. His father was a saxophonist and the leader of Supra Volta, a popular band that played West African musics with modern instrumentation, even a rhumba influence. They were active throughout the ‘60s, soon after the country gained its independence from France, and often played for heads of state and dignitaries. They were based out of an empty bedroom inside the Tarpaga household, and young Olivier couldn’t help but be drawn to their infectious tunes.

Growing up in Burkina Faso, Tarpaga didn’t have to look far to find great music. His father was a saxophonist and the leader of Supra Volta, a popular band that played West African musics with modern instrumentation, even a rhumba influence. They were active throughout the ‘60s, soon after the country gained its independence from France, and often played for heads of state and dignitaries. They were based out of an empty bedroom inside the Tarpaga household, and young Olivier couldn’t help but be drawn to their infectious tunes.

“I’d just walk there and listen to them, and they’d all walk out—somebody was smoking a cigarette, everyone was talking—and then I’d go in with my brothers and we’d start banging on everything. I was always on the drums.” In the ensuing chaos things would get broken, and as a result he was often in trouble with his father. Even so, he simply couldn’t get enough. “Music was an addiction,” he said, and though he’d repeatedly beg his father to teach him to play, he’d always be told to study his math and science, that music would have to wait. Even when his father was teaching Tarpaga’s brothers to play saxophone—despite their total lack of interest—he was still pushed to focus on math and science. Nowadays, he’s the only musician in the family.

Tarpaga’s instrumentation of choice is percussion. He’s a master of the djembe as well as an unconventional virtuoso on the calabash, a large gourd utilized for many different instruments in West Africa traditions that also serves as an excellent drum. Back in 1995 when Tarpaga first came to the US he formed his still active musical outfit, the largely drum-based ensemble Dafra Drum. Named for the Dafra River, one of Burkina Faso’s most sacred rivers located in the city of Bobo Dioulasso, the group performs traditional dance and drumming from the Djeli/Griot tradition of West Africa. Tarpaga says he felt he had to attach “drum” to the name to make their musical identity clearer to Western audiences, but playing into uninformed notions of “African music” unfortunately opened the door for stereotyping. “I’d go to so many countries where there’d be a company from Brazil, a company from the US, a company from Japan, and then we were the company from Africa. I’d say ‘Why do you say Africa? Why do you think Africa is just Africa? You speak African? There’s nothing called African.’”

Tarpaga’s instrumentation of choice is percussion. He’s a master of the djembe as well as an unconventional virtuoso on the calabash, a large gourd utilized for many different instruments in West Africa traditions that also serves as an excellent drum. Back in 1995 when Tarpaga first came to the US he formed his still active musical outfit, the largely drum-based ensemble Dafra Drum. Named for the Dafra River, one of Burkina Faso’s most sacred rivers located in the city of Bobo Dioulasso, the group performs traditional dance and drumming from the Djeli/Griot tradition of West Africa. Tarpaga says he felt he had to attach “drum” to the name to make their musical identity clearer to Western audiences, but playing into uninformed notions of “African music” unfortunately opened the door for stereotyping. “I’d go to so many countries where there’d be a company from Brazil, a company from the US, a company from Japan, and then we were the company from Africa. I’d say ‘Why do you say Africa? Why do you think Africa is just Africa? You speak African? There’s nothing called African.’”

This frustration over the years led to the creation of Dafra Kura Band in 2011, “kura” meaning new. Tarpaga wanted to present the musics of contemporary Africa, the musics bumping in the clubs of his native Burkina Faso. Whereas Dafra Drum is about 70% drum-based, Dafra Kura Band is only about 20% drum-based, aimed more at showcasing the other beautiful acoustic instruments that have been a part of many West African cultures for centuries and continue to be integral to their musics. The band’s sound fuses styles like afrobeat, desert blues, and hip-hop, among others, in turn defying easy classification. This is, perhaps, in part because of Tarpaga’s wonderfully cavalier approach to music making.

This frustration over the years led to the creation of Dafra Kura Band in 2011, “kura” meaning new. Tarpaga wanted to present the musics of contemporary Africa, the musics bumping in the clubs of his native Burkina Faso. Whereas Dafra Drum is about 70% drum-based, Dafra Kura Band is only about 20% drum-based, aimed more at showcasing the other beautiful acoustic instruments that have been a part of many West African cultures for centuries and continue to be integral to their musics. The band’s sound fuses styles like afrobeat, desert blues, and hip-hop, among others, in turn defying easy classification. This is, perhaps, in part because of Tarpaga’s wonderfully cavalier approach to music making.

While many calabash players use their hands or tools like special percussive rings, Tarpaga prefers chopsticks, something his kora player—a master Griot, or West African historian, storyteller, poet—claims to have never seen before. This is exemplary of the imaginative, unconventional creativity Tarpaga exhibits in his music. Though a highly skilled percussionist, he didn’t study music in an institutional setting and thus never learned about composing for other acoustic instruments. Instead of notating each players parts, he vocalizes the sounds rolling around in his head and his virtuosic bandmates translate his vision to their instruments. This wouldn’t work nearly as well if it wasn’t for the clear chemistry between the performers, as well as Tarpaga’s impressive ability to vocalize complex, speedy rhythms and tones. It’s a much more collaborative, joyful process than we are often led to believe the composer-musician relationship looks like, and that kind of spontaneous energy is infectious and something that lends itself to the creation of movement and theater.

For Declassified Memory Fragment music has been, from the beginning, and integral aspect of the piece. “All rehearsals have dancers and musicians, since day one,” Tarpaga says. Though it sometimes made for a chaotic process, forcing him to jump back and forth from playing composer to choreographer, the results are tremendous. More than other traditions of music and dance, in many West African nations the two are truly intertwined. A dancer won’t feel the immediacy, the tension of a centuries-old traditional war song if the kora that’s sounding it is playing off of a CD through boom box speakers. With music this spirited, this beautiful, this present, this engrossing and movement to match, they had to materialize together, have to coexist on stage as they do.

For Declassified Memory Fragment music has been, from the beginning, and integral aspect of the piece. “All rehearsals have dancers and musicians, since day one,” Tarpaga says. Though it sometimes made for a chaotic process, forcing him to jump back and forth from playing composer to choreographer, the results are tremendous. More than other traditions of music and dance, in many West African nations the two are truly intertwined. A dancer won’t feel the immediacy, the tension of a centuries-old traditional war song if the kora that’s sounding it is playing off of a CD through boom box speakers. With music this spirited, this beautiful, this present, this engrossing and movement to match, they had to materialize together, have to coexist on stage as they do.

—Hugh Wilikofsky