Chopin’s Time is our Time by Barbara Milewski

Barbara Milewski is Associate Professor of Music and Chair of the Department of Music and Dance at Swarthmore College. In anticipation of CHOPIN WITHOUT PIANO (premiering at Swarthmore College before its run at FringeArts on October 24th), she shares her musings on the mysterious Fryderyk Chopin and his relevance to the here and now.

Barbara Milewski is Associate Professor of Music and Chair of the Department of Music and Dance at Swarthmore College. In anticipation of CHOPIN WITHOUT PIANO (premiering at Swarthmore College before its run at FringeArts on October 24th), she shares her musings on the mysterious Fryderyk Chopin and his relevance to the here and now.

It took not only Chopin’s remarkable talent but also the circumstance of his self-exile in Paris to establish the value of his music within the larger world of European culture during the first half of the nineteenth century. Since then, we have grappled with Chopin’s identity and his music’s meaning. Who exactly was Chopin? A Pole, a patriot, a composer of achingly beautiful piano music, a frail consumptive, a lavender-glove-wearing dandy, George Sand’s lover, a musical iconoclast, one of Paris’s most legendary artists. Frédéric or Fryderyk? He remains mysterious, an enigma, even today.

Chopin, the historical figure, will likely continue to be whatever we most need him to be: a national symbol of Poland, a musical genius, a Parisian Romantic, a brand of vodka, a rebel. But his music will always be this: a poetic reflection of the dislocation so many Europeans felt in the aftermath of the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars and decades of uprisings and revolutions that spared no corner of the continent. Like so much cultural production of that time, Chopin’s compositions elaborate both the idea of a “new” order and the theme of a simpler old-fashioned countryside, where graveyards and abandoned manor houses preserve memories of an unrecoverable past.

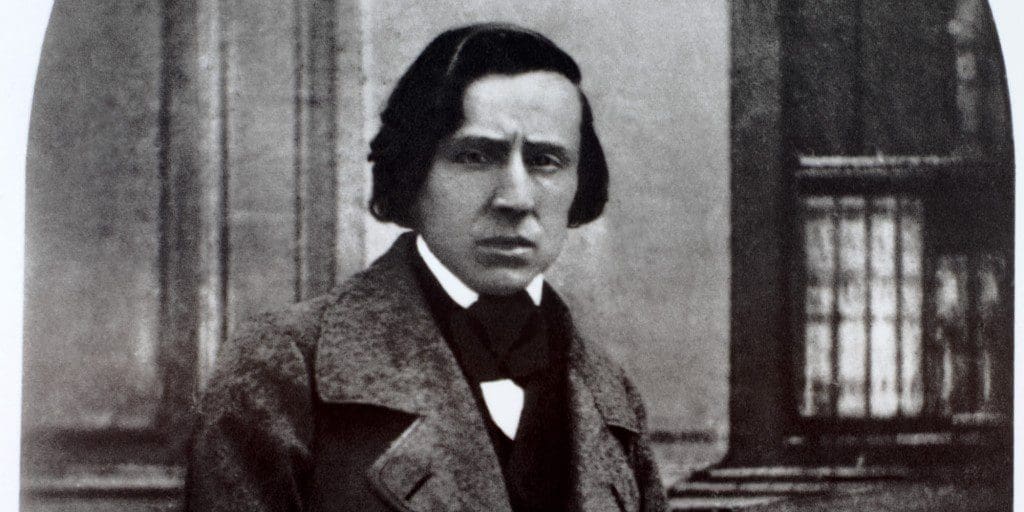

The only known photograph of the famous Polish pianist and composer, taken the year of his death (of tuberculosis) in 1849. Reproduced from a private collection.

That is why in so many of Chopin’s compositions (not least the concertos!) we encounter not a simple episodic narrative—a sequence of events in real time—or even the unfolding of a familiar dramatic structure such as sonata form or rondo. Rather we experience the musical equivalent of rifts in the fabric of the universe. Chopin molds musical matter into time’s unpredictable arrow, transporting us from one spot on the space-time continuum to another. Sometimes he just makes time stand still. But while there is a shocking sense of spatial and temporal discontinuity at work, Chopin tenderly passes it all off as part of music’s ordinary process of unfolding—a would-be daydream.

Chopin’s music is a meditation on time. And because our sense of time has not changed much since his day (it insists on marching inexorably forward, perhaps just at a faster pace than before), Chopin’s displacement is our displacement, his music a refuge that is now our own, his cultural-artistic production a source from which we draw inspiration to create new artworks. That’s the great thing about great art: it remains valuable because it is enduringly human; we recognize our own selves in it. And when we hear his compositions over and over again they become sort of like our home—that place of comfort and familiarity to which we return amidst our wanderings.

CHOPIN WITHOUT PIANO experiences its U.S. Premiere at Swarthmore College on October 24, followed by a run of performances at FringeArts October 28-31. For more information or to buy tickets, visit www.ChopinWithoutPiano.com