I Like America and America Likes Me: A Meditation on Performance and Violence

“When you’ve begun to think like a gun / the days of the year are already gone.”

—John Cale, “Gun”“John Kennedy shot John Wilkes Booth in the heart. Booth went to a farm bleeding. He ate a live cow. Kennedy found him and shot him with Kotex. He shot him in the Goddamn fucking empty American heart. He shot him with McGeorge Bundy. He shot him with Arthur Schlesinger. He shot him with miracles and master plans. He shot him with everything. Everything has 13 or 26 or 89 letters. Kennedy, Booth, Oswald, Ruby and Lincoln are all dead.”

—Bill Hutton, A History of America

In 1974, Joesph Beuys came to New York and spent three days living with a coyote in the Rene Block gallery. Beuys titled his performance Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me. Of the show, Beuys, ambivalent about the United States and its role in global warfare and perpetuation of violence, said, “I wanted to isolate myself, insulate myself, see nothing of America other than the coyote.”

Beuys fashioned himself a mystic, a shaman, and he hoped in some way to commune with what, perhaps, he saw as the spirit of America, the coyote, the spirit with which Americans themselves were (and are) at war. According to David Levi Strauss, Beuys “engaged the coyote in a dialogue to get to ‘the psychological trauma point of the United States’ energy constellation; namely, the schism between native intelligence and European mechanistic, materialistic, and positivistic values.” The investigation has been framed as one of artistic authority. But in its connection to the United states, the question regards authority more broadly.

Aspects of this schism pervade United States culture. The coyote is reviled by ranchers, for example, as an agent of chaos; but we also laud the coyote for its freedom to roam the United States heartland, and in some way, respect its ability to resist and adapt to our attempts to exterminate it. This tension—between what we understand (and desire) as pure freedom and what we accept (or inflict) as order—undergirds how we think about what it means to be American. And that includes how we think about our gunmen.

After the jump: the duplicity of terror, and getting free.

Everybody, everywhere now knows about the murderous rampage that took place Thursday night to Friday morning at a screening of The Dark Knight Rises in Aurora, Colorado. Based on published reports, this assault was not an exercise in sowing chaos; rather, it was an exertion of control by the shooter. And as with nearly all acts of terrorism, it was successful. Rippling out: enhanced security at movie theaters, the cancellation of the Paris premiere, and questions, again, about whether we can ever be safe—all of which blossom from the seeds of fear. In its responses, the state believes that it can maintain a grip on terror; the state is not aware that terror, instead, grips it. Or, perhaps more cynically, the state could be all too aware—hence the emergent term “security theater.”

In the United States, of course, the state is us. We, therefore, are at once both the authors of and audience for the grandest work of devised theater imaginable. In this way, every day, through our politics, our relationships—and our guns—we perform what it is to be American. To answer the Jezebelian question “What is wrong with us?”—we are a violent people. Guns don’t kill people. Americans kill people.

However, I shouldn’t say American here. Other Americans—South Americans in particular—hate that the United States lays claim to being America. The reason we use the term, I believe, is that as a nation we do not have an single ethnic identity. A few weeks ago, over many drinks at a bar in Santiago, Chile called Road House, where Patrick Swayze’s “Road House” played on the second-floor television, my new friend Patricio and I agreed that I was not an American, but a United Stater.

As Max Read wrote on Gawker, these type of tragedies cannot be politicized because they are necessarily political.* Political forces and exigencies are the reasons that the alleged shooter in Colorado could legally purchase an assault rifle, oversized clips, and thousands of rounds of ammunition. For many, preserving our ability to deal death is fundamental to what it means to be American.

And this alleged shooter performed that America. Regardless of whether he was mentally ill, regardless of whether he felt in a sick mind that he was defending himself or whether he just wanted to kill without mercy as many people as he could, we, through our politics, enabled him. THIS IS WHO WE ARE.

And we know this. From Slate to The Onion to The Atlantic, we understand that these crimes are inexorable, inevitable, and increasingly common. And we mourn not only the victims of this act of terror, but, finally, ourselves. We have come to know that not only will there be a few mass shootings every month, but also that we will react in certain ways, and that we will do little to solve the problem. Collectively, at least since Columbine, and perhaps for longer, we have moved through the stages of grief; this time, we begin to reach acceptance. THIS IS WHO WE ARE.

But let us leave that America behind, and embrace each other as United Staters. We already do this here and there, in drips and drabs. About this shooting, Dark Knight Rises director Christopher Nolan wrote, “I believe movies are one of the great American art forms and the shared experience of watching a story unfold on screen is an important and joyful pastime. The movie theatre is my home, and the idea that someone would violate that innocent and hopeful place in such an unbearably savage way is devastating to me.” At ThinkProgress, Alyssa Rosenberg wrote that the outsized midnight screenings—the massive and mass cultural movie events—still, in some way, remain “a product of genuine enthusiasm and an expression of collective joy.”

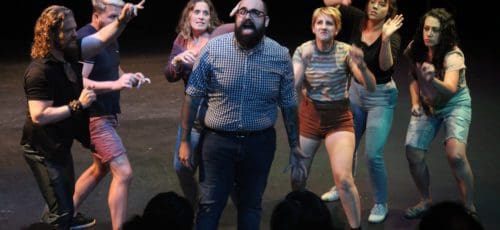

Because this, too, is who we are. Nolan sees the movie theater as a innocent place, but such spaces are more than innocent: they are spaces of artistic communion, of collective witnessing, of collective action, and yes, of collective joy. These spaces—movie, music, theater, and dance venues—have become radical spaces, spaces that resist the death cult of performing America. Spaces where we commune in ways that are rare, and precious. This is why we do what we do.

This is why in their bio, Applied Mechanics states that they eat a meal together at every rehearsal. This is why four households are opening themselves up to Headlong, and to us. This is why we’re going to Bruce Walsh’s house and the Hacktory and to drink during shows at The Dolphin Tavern and a go-go bar and Quig’s and to a cabaret in a graveyard and to make spotlights dance on the Parkway. It is not just in venues that we can commune—it is everywhere.

In these ways, we can resist the madness of performing America. It is time to leave behind that death cult. It’s time to stop thinking like a gun. We are not some kind of Schroedinger’s cat, bifurcated by a cocked hammer that limns dead and not dead. We are not “not dead,” but instead, we are alive. This is why we do what we do. We are not Americans, but United Staters. We are alive and we are United Staters and our days are still here and they are ours to share and we love you.

–Nicholas Gilewicz

*Any political opinions accidentally expressed here are solely those of the author, not of the Philadelphia Live Arts Festival and Philly Fringe, just so we’re clear.