That Show That Makes Me Think of Bing Crosby: Samantha Pearlman’s “Devotedly Sincerely Yours: The Story of the USO”

The director tells the actress to pause. She backs away from the microphone. The director sidemouths a comment to the lighting designer, who considers it, then nods. The director turns her gaze back to the stage, and tells the actress to take a step towards stage left; here, she says, her hair will catch the light—catch it in such a way that there is a buoy of yellow: a halo.

Look again. A young woman—walnut, curly hair and green eyes—talks to herself. She’s acting one moment, then running off stage the next, sitting in the audience to direct the role she has just left—trying to wrestle a phantom it seems.

Why is she doing this? Is she insane?

Samantha Pearlman is not insane. The enthusiasm with which she speaks is a thrice-churned product—one part ambition, one part intelligence, and one part love. Perhaps then, she is lesser-than-sane; but, she is not insane. That adjective she saves for her decision to research, write, direct, set design, produce, and star in the original run of a one-woman musical, Devotedly, Sincerely Yours: The Story of the USO. “I needed to do everything. I needed to try wearing all those hats,” Samantha said.

For this year’s Philly Fringe in steps Kate Galvin, former casting director at the Walnut Street Theatre (she also recently directed Proof at Walnut Street Theatre’s Studio 3), to spare Samantha the pangs of overcommitment and to add her touch of brilliancy. “These past couple of weeks I’ve been rewriting, revisiting the script, changing some things, making things better with Kate’s help,” Samantha said. She is grateful for Kate, the sincerity of her thanks unmistakable because of her sighs, the admissions — “I’m so lucky to have her,” Samantha said — and the vivid memory of DSY‘s full-throttle genesis: “Usually during tech week the director is in the audience with the designers looking at each lighting look, and saying, ‘I like that. I don’t like that. That change is weird. It has to be slower.’ I’m on stage. I can’t see any of this. It was so insane.” A circus performer trying to juggle her own limbs.

After the jump: Wild claims about Wesleyan University, and stories of the women of the USO.

It was all for the academy (that other one) though: DSY debuted in April of last year, the performance component of a two-part undergraduate thesis submitted to the theater department at Wesleyan University, known more commonly as The Best Place on Earth. (Note: This is not an official moniker for the university. This author is a fellow graduate. Despite the slip, she maintains her objectivity on all topics non-Wesleyan.) The other half of her senior capstone? An analytical paper, entitled “‘Something for the Boys’: An Analysis of the Women of the USO Camp Shows, Inc. and their Performed Gender,” weighing in at 97 pages.

Despite its heft, the research component was inspired by a much shorter text, one that Samantha found while conducting research at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center the summer before her senior year.

“I found this letter in the archive that really prompted my project, that was by this woman named Louise Buckley,” said Samantha. She neglected her iced coffee as we talked in La Citadelle, a corner cafe near Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square. The barista is a French-speaking (well, he said merci) man, stocky and bald-headed, whose practice of greeting each customer with a flirtatious remark belied—at least, in my case—the frequency of their patronage. Samantha, though, is a regular: the real deal.

She described in detail Buckley’s letter: eight pages, single-spaced, typewritten. “She’s stationed somewhere in New Guinea and she’s probably around my age, and she’s just describing with painstaking detail all of her experiences overseas and it’s so beautifully written. When I finished reading it I was so floored by the imagery, and the drama in the letter, and just how moving her experience was that I just knew, I have to find out more about these women and who they were and what they did.”

These women were American Broadway, radio, and movie stars and they performed overseas as part of the USO live entertainment. The USO, or The United Service Organizations, is a nonprofit, private organization founded by the U.S. Congress. Its mission today, as it was defined when the organization mobilized in 1941 at the sound of European conflict, is to maintain a high level of morale among American troops and their families. Samantha’s show is based on one of the services the USO provided in the 1940s: Camp Show Inc., a chapter that was discontinued after World War II.

“What they would do during the 1940s was provide ways for the men to play sports, maybe go to church or some kind of religious service, they would provide some food, they would provide letter-writing stations, try to get mail to them, and they would provide live entertainment,” says Samantha. The piece focuses on the female performers who headlined many of these live shows, and the implications of being, in some cases, the only American woman for miles and miles.

“They embodied ideas of home for the soldiers; they embodied the American sweetheart ideals. A lot of times they would serve food to the soldiers, they fixed their uniforms, they would sit and talk with them, dance with them, be this almost wife-like character for the men, both on stage and off,” Samantha said, recalling her paper.

“These women were hired to just remind and fulfill the mens’ dreams and fantasies of all their female relatives, of sisters, mothers, girlfriends back home. In the letter [Buckley] says, ‘Every woman back home wears a halo in these boys’ minds, and so it’s up to us USO entertainers to maintain that halo.’ I just love that image—the simultaneous gift that it is, but also the burden of maintaining a halo.”

The voices of these women, compiled through arduous archival research, comprise Samantha’s character, a female entertainer the audience comes to know through her appearance on a live broadcast of a radio show. These were often recorded and sent overseas for the men to play, as if hearing them in real-time.

Skype sessions have since replaced radio recordings and letter-writing stations, and Samantha contends that when American soldiers today watch USO contemporary female performers—among them country singer Kellie Pickler and singer-songwriter Colbie Caillat—they are less likely to cast them as their wives, or girlfriends: “The men can pick up their phones and look at their girls, rather than just clutching onto a really tattered photograph. The pace of it is different,” she says.

“The amount of male gaze on the female body” hasn’t changed much with the march of technology, Samantha insists. “[Today] I’m sure the men hoot and holler at [the female performers] because they’re beautiful and they’re talented and they’re there for the boys.” In the 1940s, she says, female performers “embodied ideas of heterosexual fantasy and sexual object for the soldiers. They would wink, wink, nudge, nudge, on the stage and most of them were very beautiful and slender and had a very pin-up quality to them, so they could embody this fantasy as well.”

Fantasy, a heightened sense of reality, often collides with it as well; overseas travel in the 1940s was dangerous, and these women risked their lives even before getting to the stage. Samantha told me the story of Jane Froman.

“She was a pretty famous Broadway, radio, and screen star of the time,” Samantha said. “She gets on an airplane [en route to a USO performance], and the airplane crashes on the way overseas and it lands into a river near Lisbon. Jane and the pilot were the only people that survived this plane crash, and they take her to a hospital in Lisbon and her leg is completely mangled, its just completely useless. She didn’t want to have it amputated—she’s a performer, this is her livelihood. If your leg is destroyed your career is in a little bit of trouble. She gets put on a boat—she can’t be flown back home because of her leg—and she finally gets home months later, and the government won’t pay her medical bills.”

At this point in the recording of our conversation, the thick Frenchman—the cafe’s personality and owner—ups the volume on a bold play list of Spanish guitar, and I’m hard-pressed to hear the tale of Froman’s injury. Sitting on a wooden bench against a two-toned green wall, like a field whose northern corridor is marked by slight drought, Samantha seems not to notice.

“The way for [Froman] to make her money is by performing. So she does a Broadway show where she is carried on and off stage 30 times throughout the course of the play—some stagehand would come out and pick her up and carry her on. [Then] this crazy woman goes back overseas and does a whole USO tour without the use of her leg,” Samantha says.

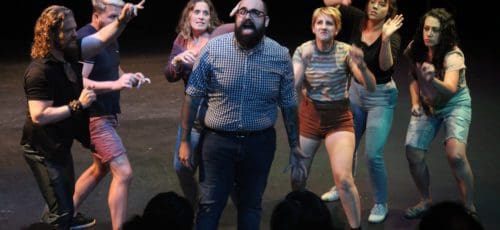

Before she had to leave (to catch a bus to New York City), I prodded Samantha for an anecdote, something to sum up the crazed process of writing a nearly 100-page paper, only to have it inform another writing project: a full-length play. She laughed, remembering the frenzy of concurrent onstage and offstage roles: “There would be certain cues where I’d have one of my girls, that were my stagehands, step in for me. I would go out in the theater, look at it, then change things, go back, keep running the show.”

As she spoke, I pictured Samantha staring at the stage, trying to impress her own character, a composite of Buckley, and Froman, and countless other women, on an unwilling, at times nonexistent, frame. I thought of the stagehand—a young student, perhaps baffled, and nervous, and not sure what to do—trying hard to carry on stage Samantha’s vision, at once luminous and determined.

Devotedly, Sincerely Yours: The Story of the USO runs September 6 and 7 at 8:00 pm, and September 8 and 9 at 2:00 pm and 8:00 pm at The Off-Broad Street Theater at First Baptist Church. 1636 Sansom Street. $18.

–Audrey McGlinchy