Tales of darkness shot through with light: Brett Bailey & Third World Bunfight

This weekend FringeArts and Opera Philadelphia will present Macbeth as part of the 2016 Fringe Festival. A reimagining of Verdi’s nineteenth century opera from South African theater company Third World Bunfight, this production brings the classic tale of greed, tyranny, and corruption to the Democratic Republic of the Congo where a brutal warlord and his ambitious wife murder the king and unleash atrocities on the crumbling province that they seize. For more info and to purchase tickets click here.

Brett Bailey and his company Third World Bunfight have been making iconoclastic, politically-charged theatre in South Africa since 1996. Driven to tell “tales of darkness shot through with light” and inspired by what he calls the “addictive funkiness” of African aesthetics, his work concerns Africa’s post-colonial dynamics and the historical and contemporary relations between Africa and the West. His work is eclectic in style and syncretic in form, weaving together African spirituality, a fascination with pop culture, a strong visual design drive, the belief in theatre as a communal space of potential and transformation, and an acerbic political critique. Utterly intolerant of cruelty, oppression and injustice, he believes that theatre has to be rooted in social and political issues, serving a purpose other than pure entertainment, without being the slave of such agendas. And finding a balance between social critique and aesthetic beauty and atmosphere in a work is his constant goal as a theatremaker.

He plays in worlds of risk and liminality, where ritual meets theatre and ceremony and presentation collide. “Liminality, the sacred, places of paradox and confusion, border zones where anything can happen, contested territory and risk are the areas I like to work in,” he says. He aims to inject spirit into theatre and to “unpick the threads” of fear and racism that divide people.

Born in 1967 as a privileged child of apartheid, Bailey studied drama at the University of Cape Town (UCT) and graduated in 1991 into a transforming political climate. After a year of spiritual searching in India in 1994, South Africa’s transition year, he joined the New Africa Theatre Project, whose goal it was to create work that spoke to the burgeoning new democracy. In 1996, Bailey immersed himself in Xhosa ritual, folklore, and performance, training with and living at the rural home of sangoma (traditional healer) Zipathe Dlamini in Port St. Johns in the Transkei.

His early career was marked by large-scale, immersive Dionysian performances that emphasized theatre as a communal space. In site-specific works like Ipi Zombi? (1998), The Prophet (1999) and Orfeus (2006), he created spaces in which diverse audiences could cross the borders the apartheid state erected to keep people separated. “With the de-spiritualisation of the West,” he claims, theatre lost its sense of communion. Bailey sought to create theatre that is “rich and thriving and humming like a Hindu temple…or a voodoo ceremony, with people flipping into trance, chanting and sacrificing, dust and blood and beer and gods.”

These early works blurred the lines between theatre and ritual, and between African and European forms. Audiences were immersed in performance experiences involving incense, incantation, sangomas in trance, masked actors, and mythic stories of witchcraft (Zombie 1996), South African colonial history (iMumbo Jumbo 1997, The Prophet 1999) and spiritual journeys into spaces of otherness (Orfeus 2006).

In his evolution as an artist, Bailey has recently tightened the scale of his work, creating performance installations featuring tableaux vivant that facilitate an encounter between a single audience member and the performance she or he experiences. Works like Terminal (2009) and Exhibit B (2010-2016) imagine the power of theatre lying in individual spectators’ negotiation with the spectacle before them and places the real power in the scenario on the actors’ gaze over the audience. The transformation in his style and the form his work takes have mirrored the country’s transformation out of apartheid and into the new democracy.

Bailey is a visually-motivated artist and his creative process involves immersive research residencies, the selection of site-specific spaces, a strong design aesthetic driving his work, and a performer-centered approach. Orfeus was performed in an old quarry that audiences had to trek to, and through, to encounter performers in various scenarios of the underworld; in Terminal audiences were lead by small children around Grahamstown’s now-defunct railway station, the township across the tracks, and the 1820 settlers cemetery; and Exhibit B has been staged in museums, libraries, old churches and other sites of colonial knowledge production across Europe.

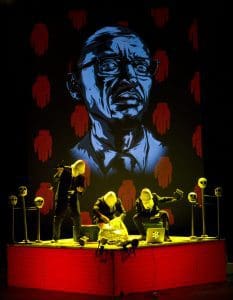

In all his work, Bailey wrestles with human relationships to power; he often creates dictator characters and explores their abuses of power or marginalized people and communities and the systems that oppress them. In the “grotesque cabaret” Big Dada (2001), he focused on Uganda’s Idi Amin as a stand-in for Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe. In Exhibit B, he explored Europe’s objectification of African bodies in the 19th century practice of human zoos. Macbeth (2014-2016) sets Shakespeare’s tale of greed, bloodlust, and political maneuvering in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where a corrupt government, ruthless militia, and multinational corporations conspire to tear the region apart. An adaptation of Verdi’s opera, Bailey’s Macbeth critiques the global appetite for minerals used in cellphones, DVD players, laptops, hard drives, and gaming devices and the terrible price they demand of Africa and Africans. Macbeth’s rich visual codes include Dutch wax fabrics infused with the iconography of global capitalism, an altar-like stage, and the flattened, colorful style of Congolese painting.

Making provocative, syncretic work that draws from multiple cultural registers, embraces paradox and change, and asks audiences to encounter difference comes at a price: Bailey is a man people love to hate. His early work was critiqued for appropriating African spirituality and forms, and he triggered outcry as a white man working in black African realms. In 2014, his powerful installation that interrogated the European colonial relationship to black and brown African bodies—Exhibit B—was shut down after protests in London and Paris. Protestors read Internet images of the show as racist and cast Bailey as a white South African bully oppressing inert African actors, playing into an easy and familiar master-slave dialectic that people felt righteously indignant about. By placing all the attention on Bailey, the man, at the expense of the work itself, the protests ignored the powerful agency, free will, and motivations of the ensemble of actors who are the core of the work. The censoring of Exhibit B was a case study in the limits of clicktivism and racially charged representation; the production became a lightning rod for European racial tensions around African migrants in the current refugee crisis.

Bailey is currently working on a piece about the European refugee crisis he is calling Sanctuary. Structured as a labyrinth audiences will have to navigate, it will involve tableaux vivant and his signature performance provocations that feature live actors engaging migrating audiences face to face, eye to eye, human being to human being.

—Dr. Megan Lewis

Dr. Megan Lewis is a South African-American theater historian and performance scholar concerned with the staging of national identity, gender, and race. She is the author of a monograph about the intersections of whiteness, masculinity, national identity, and performance in South Africa, Performing Whitely in the Postcolony (2016) and Magnet Theatre: Three Decades of Making Space (2015), a collection of essays and interviews about Cape Town-based Magnet Theatre. She is an assistant professor of theater history and criticism at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.