Moving Against the Tides with Olive Prince

“In watching the tide and the ocean, I think a lot about how it slowly and suddenly shifts. You have to look at it closely, but it totally changes, from the beginning of tide to the end of tide. And I hope I do that with this space.”

Olive Prince founded her dance company in 2008, and since then, has been devising, creating, and teaching highly dynamic works of art. Olive Prince Dance (or OPD) works are often site-specific, such as past productions in the Magic Gardens and in the Iron Factory. For this year’s festival, however, the show is held in the Ballroom Philadelphia, and she is working with visual artist Carrie Powell as a conceptual collaborator for the show. Carrie is building a sculpture that will create an entirely new type of space for the dance. The show, called Silencing the Tides, is a work that exists under and around a large sculpture fabricated from clothing. The show is based on the idea of free will, juxtaposed with messages and metaphors from nature. She evokes strong images of the ocean’s tide, many of the ideas growing from the feeling of sand and the changing nature of the waves. The dancers sway between working together as large forces, and breaking out into their own movements. Sometimes calm, sometimes violent, they may break down barriers as if they were bodies of water, or they may escape each other as if they were sand.

Olive and Carrie are close friends, and the idea for Silencing the Tides grew out of conversations they had together last year. “We’re both artists, and we’re both mothers, and we often spend time together with our kids talking about art.” Carrie often writes poetry and creates drawings to go along with the ideas. She started making drawings that looked like piles of laundry. They talked together and started thinking about ideas of free will, as well as the forces of nature. Olive was drawing inspiration from literature she was reading, including “The Things they Carried” by Tim O’Brien:

“They did not submit to the obvious alternative, which was simply to close the eyes and fall. So easy, really. Go limp and tumble to the ground and let the muscles unwind and not speak and not budge till your buddies picked you up and lifted you into the chopper that would roar and dip its nose and carry you off to the world. A mere matter of falling, yet no one ever fell.”

She also brought in pieces of The Venerable Bede, from 703 CE (“The most admirable thing of all is this union of the ocean with the orbit of the Moon…the sea violently covers the coast far and wide…unwittingly drawn up by some breathings of the Moon.”) as well as Johnathan White and Mary Oliver’s short story, “Swoon.” “I had this really strong image of free will,” she says, “and going against the tide, and so we started exploring that.” Eventually the conversation between Olive and Carrie became the basis of the work. These conceptual conversations combining ideas from movement, visual art, poetry, are integral to the creation of new work, and it has become a defined process that they call in-the-round reciprocity.

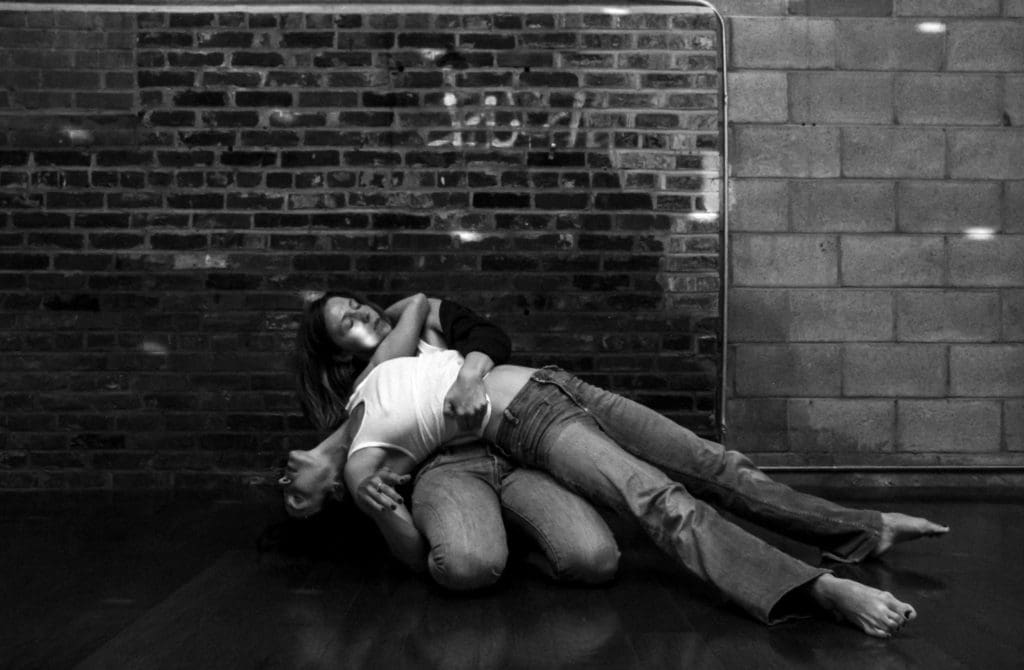

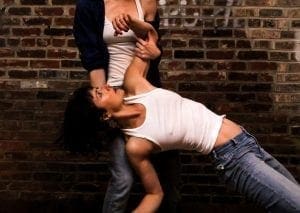

As tides slowly move around the sand on a shore, this show is also about transformation. One section includes an “anchor duet,” where one dancer acts as the “anchor,” while the other is constantly attempting escape, moving like a pile of sand. “It’s a little violent sometimes, to become something, which happens in the birthing process, which happens in your own process of becoming who you want to be in the world. And this happens in water. It’s a life giving force, but it’s violent and dangerous. So there’s that dichotomy: how do we find it physically?” The dancers move between throwing each other and catching each other, sometimes supportive, other times letting each other fall. The pile drawings that Carrie created are a part of the show, and are sometimes scattered on the floor. The sculpture, however, remains untouched, and constructs a new component of the environment. “I feel like we’re living in a world under it,” says Olive. The dancers move in different directions, creating evolving compositions on the stage that slowly change. Like the pile drawings, their bodies are made into piles, sometimes very still, and sometimes full of movement, almost like Alexander Calder’s mobiles. The space is small, and audience members can sit at many different angles, right up close to the dancers. “I love the idea that an audience member could see it more than once, and have a different experience with it. The experience of it is like a sculpture.”

Olive is originally from Rochester, New York, and came to Philadelphia for her MFA in 2002 at Temple University. She had been doing modern dance since high school, and loved the vibrancy and creativity of the city. The dancers in the program often influenced each other, often in watching each other commit to the difficult process of becoming an individual, creative artist. “It was a time to really immerse and be an artist, to really learn. That’s where I met Merián Soto, who’s been a huge influence on me, and Kun-Yang Lin.” She worked with both dancers in many productions after graduating, until she decided it was time to start creating her own work. “There is a point along the way where you gain confidence in how you’re working.”

She began Olive Prince Dance in 2008, and it has remained a project based company that is always creating new work since its inception. The dancers are all women, and the company was recently on a short hiatus as three of them (including herself!) gave birth. “We came back, and three of us were three to four months post-birth. So there would be babies in the space, or someone would stop and pump, or someone would come and drop a baby off and you’d feed them. I think that really influenced the process of ‘showing up,’ and that was crucial.” Balancing between being an artist and being a parent is extremely difficult, and the creation of this show has been especially challenging. “For me, the hardest thing is having that space in your mind and in your body to have that be a practice. You’re so emotionally and physically drained from parenting. In this process more than any others, I felt like asking myself, ‘Am I quitting?’ Because if I don’t have enough to emotionally and physically give to the work, or as much as I feel that I should, is it still warranted? Does it still have value?” Having her second child, and two other dancers becoming new moms, has caused them to evolve their practice and creative process. “I want it to be good, and I want it to be real, and I want it to be fully investigated,” says Olive, “but what I’ve learned is that I have to change the notion of what those things mean.”

Olive is determined to strive forward as a full-time artist and mom. In the mornings, she often puts on music that inspires her creative process in dance, and will do floor work, often with her two young sons. The company rehearses twice a week in the mornings, and Olive also teaches part time at Drexel University. Two of the dancers are recent Drexel graduates, one teaches ballroom dance, one teaches gyrotronics, and another is a medical technician. They all have separate jobs and activities, as it’s nearly impossible to support oneself as a full time dancer. Although other jobs and new babies have made producing a show of this caliber exhausting, they all rely on each other to show up. Sometimes this fatigue works itself into the practice and into the dance itself. “It’s equal parts challenging and helpful,” says dancer Evalina Carbonell. “There are different textures in the vocabulary. When you’re exhausted, your body can reveal information to you, and it’s helpful in introducing different ways that the body moves.”

Olive teaches undergraduate dance students at Drexel, and and will be choreographing in the fall at Bryn Mawr College. “I love that age, and I love the students,” she says, “because they’re at a point where they’re searching for their artistic voice, and I work hard to help find what’s authentic to them.” She says that teaching is a lot like the improvisation of dance. “Teaching is like dancing in many ways: you set yourself up with a structure, and you follow your intuition and the energy of the group. For me, it’s very informative of my artistic practice, and it helps me in my choreographic process. They’re reciprocal.” Her teaching, along with her love of visual art and literature, form the seeds of ideas for her productions. She begins with a movement, and then draws from other forms of art. She uses visual art and images in her teaching and in the devising of her pieces. “I use it as a modality for people to express themselves.” Images of war, water, and sand, as well as drawings by Carrie Powell, all worked as these seeds for Silencing the Tides.

It was through this practice that she met the Sébastien Schuller, a composer from France. She was in the park with her son. “He was playing, and I was dancing. I was interested in how the sand moved, so I was just improvising and moving on the baseball field while my kid was digging in the dirt.” Sébastien was at the park with his child as well. They started chatting, and it turned out he had always wanted to work with dance. Today, he is composing a part of the score for the production.

Being an artist and a parent at the same time is certainly difficult, but within Philadelphia, there is a strong and supportive community of artist-parents, and interdisciplinary conversations between Olive and Carrie, as well as with Sebastien, have been essential in creating her work. “The art is becoming more and more interdisciplinary, where there almost aren’t different genres.” There could be more, however, in both work between the disciplines and support in general. Although Olive appreciates the interdisciplinary nature that the community is driving toward, “I think the training should match that, and I don’t think it can quite yet.” There is power in artists working together and raising the caliber of art in the city. “When we’re all better artists, it feeds all of us. When art in the city is better, it makes everybody better.”

This idea is especially important in 2017, as many are turning to art as political fears grow, looking for answers. Olive Prince Dance experiences this every day, in both their practice and in the work that they are producing. As women taking care of young children, they viewed the practice of showing up as something defiant. “Maybe I didn’t sleep all night, but we showed up, and we did something, even if we weren’t sure what it was,” says Olive, “and it became almost a political statement, to make it important, and to make space for you to show up as a nursing mother.” The themes of the show reflect ideas of standing up and revolting against the norm. “I can only speak for myself as a woman, but I’m seeing it, we’re living in a time where many peoples and cultures are being asked to be quieter, and they’re not as valued in our society. And that’s a problem. When it happens at such a big political level, how are we not all influenced by that?”

Silencing the Tides

Olive Prince Dance

$18 / 50 minutes

Ballroom Philadelphia

1207 Gerritt Street

Sept 16 at 5pm + 7pm

Sept 17 at 2pm + 4pm

– Isabella Siegel

Photos: Lindsay Browning (banner, first, and second photos,) and Jamie Kassa (last photo.)