Alone Together at Close Music for Bodies

I’ve found myself thinking a lot about sonic resonance lately, due in no small part to some recent visits to La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s installation Dream House. Various incarnations of this sound and light environment have been mounted by Young—a revered minimalist composer, some say the first—and Zazeela—a light and visual artist and musician— around the world since 1969. The MELA (Music Eternal Light Art) Foundation Dream House at 275 Church Street in New York City has remained in that space for the last 25 years, the couple’s longest installation to date. It is a room of infinitely repeating cycles of sound and light frequencies, one that transcends its overwhelming, lower Manhattan surroundings.

During my first visit, initially the sounds contained therein were not as pleasant as I expected, grating even. It took a few minutes to acclimate, but once my eyes adjusted to the dreamy, pink and purple hued lights and my body to the drone reverberating through it, the experience was unlike much else. Speakers are directed such that where you position yourself in the room determines what you hear. You can even opt to just sit down on the lush carpeted floors and loll your head to witness the difference, exhibiting just how spatially specific the installation is.

During my first visit, initially the sounds contained therein were not as pleasant as I expected, grating even. It took a few minutes to acclimate, but once my eyes adjusted to the dreamy, pink and purple hued lights and my body to the drone reverberating through it, the experience was unlike much else. Speakers are directed such that where you position yourself in the room determines what you hear. You can even opt to just sit down on the lush carpeted floors and loll your head to witness the difference, exhibiting just how spatially specific the installation is.

I couldn’t help but recall this experience when observing a rehearsal of Close Music for Bodies on a rainy afternoon some weeks back. The piece from sound artist Michael Kiley premieres September 20th and runs until the 24th, part of the 21st annual Fringe Festival, and much like Dream House it calls attention to the infinite amount of unique experiences that structured sound can offer in a live setting. That’s about where the similarities end. Whereas the experience of Dream House is a solitary one, Close Music for Bodies is a communal, deeply humane work that wrings beauty out of the limitations of perspective.

Central to Close Music is Kiley’s voice practice, Personal Resonance. “My primary goal with teaching is to have the student understand that the real beauty and benefit of voice has nothing to do with how you sound, and everything to do with how your voice can make you feel physically—and therefore mentally,” he recently told the FringeArts Blog. “Once someone understands how to control that physical sensation, their voice becomes as accessible as breathing.” This democratization of singing is integral to the performance and bolstered by the democratization of the space itself.

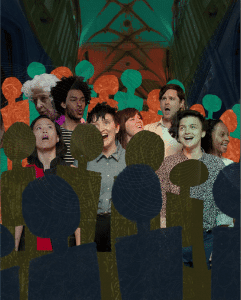

Once the piece kicks into motion, the shuffling about of cast and audience rarely ceases. At various intervals throughout the duration the performers guide audience members into various formations and in turn have to constantly navigate around them. These are all very conscious, choreographed movements, shaped with the help of choreographer Sean Donovan, director Rebecca Wright, and the performers themselves. Explaining the team’s close attention to movement, Kiley told us in that same interview, “I’ve been thinking of the movement as sound design—like speaker placement, only my speakers happen to be performers.”

Where one ends up placed within the space dictates how they experience the music, and even when audience members are packed together tightly, the performers find interesting ways to emphasize the specificity of what you’re hearing at any particular moment. This inclusive/exclusive dichotomy is also played out in the conveyance of the piece’s lyrical content. Fragments of deeply personal, captivating memories are impressionistically woven together, but are not always relayed by all the singers at once. When this first occurred I found myself straining to catch everything singers across the room were sharing with audience members at a better vantage point, but my initial curiosity was soon tempered by the realization that I wasn’t meant to hear it all.

Where one ends up placed within the space dictates how they experience the music, and even when audience members are packed together tightly, the performers find interesting ways to emphasize the specificity of what you’re hearing at any particular moment. This inclusive/exclusive dichotomy is also played out in the conveyance of the piece’s lyrical content. Fragments of deeply personal, captivating memories are impressionistically woven together, but are not always relayed by all the singers at once. When this first occurred I found myself straining to catch everything singers across the room were sharing with audience members at a better vantage point, but my initial curiosity was soon tempered by the realization that I wasn’t meant to hear it all.

It’s rare that a musical performance emphasizes the fact that no two audience members are having the same experience. In general, performances are designed to ensure a shared experience—or a as close as possible approximation of—is delivered, but the truth is that as an audience member, once a performance kicks off, you’re alone. Though you might exchange excited glances—or if you’re particularly rude, words—with a friend during the duration, in the end it was not a literal shared experience. After all, what is?

Close Music for Bodies highlights this isolation, but in a manner that doesn’t make you feel alone, quite the opposite. Whereas my experiences at the Dream House brought about some deep introspection, Close Music took me out of my head and made me curious about and engaged with the performers, my fellow audience members, everybody around me. We can never share everything with each other, but that just means there is always more to know, always an opportunity to get closer.

—Hugh Wilikofsky

Close Music for Bodies

Michael Kiley

Sept 20 + 21 at 7pm

Sept 22 at 6:30pm

Sept 23 at 6pm

Sept 24 at 4pm

Christ Church Neighborhood House

20 North American Street

$29 general

$20.30 member

$15 student + 25-and-under