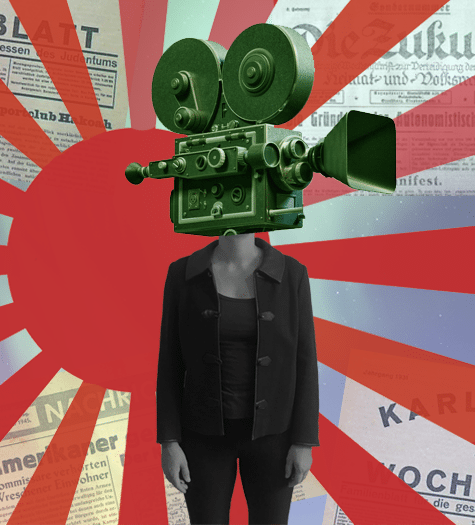

Portrayal of Displacement: A Spanish Civil War Film and The Propaganda Machine

We live in a world of refugees, from asylum seekers, to immigrants seeking to build a better life, to camps and shantytowns full of the forgotten. As events on phones and televisions are relayed around the world, we have become desensitized to images of displacement. Refugees are the norm rather than the exception of social-political-environmental wars.

The current “immigration debate” in the United States exemplifies the inhumanity that characterizes contemporary policies and discussion. Refugees who have gone through so much experience further humiliation — family separation, a First Lady wearing “I don’t really care, do u?” at a detention camp for children. These are the reactions to a legitimate worldwide crisis.

Awaiting Refuge

Fringe Festival piece The Propaganda Machine Show (I’m the artistic director) looks back at the first major refugee crisis in the world to be covered by “modern media” — the plight of Spanish Republicans in the late 1930s — by examining one of the first pieces of cinematic documentation of a humanitarian crisis.

As Spanish fascists prevailed in the bloody civil war, Republican refugees who fled their native soil were put in camps, imprisoned, and humiliated. Although the cause of the Republicans was not officially supported by any democratic country, many citizens from around the world, including the United States, volunteered to fight in Spain as part of the International Brigades. However, once the fascist regime was officially established at the end of the war in 1939, humanitarian efforts to help the Republican cause waned.

In an attempt to convince the United States public that the Republicans still needed their support after the war, the New York Office of the Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign (SRRC), a subset of the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, prepared numerous projects. These included the feature film Refuge, a shortened and dubbed version of the documentary Un peuple attend (A people is waiting) by Jean Paul Le Chanois (alias Jean Paul Dreyfus).

The longer version of the film combined original footage, newsreel, and even images subversively taken from a camera hidden in a grocery bag. The shortened Refuge was intended as a means to raise funds and awareness of the humanitarian consequences of displacement.

French director Le Chanois (he changed his name from Dreyfus — or Dreyfuss in German — to avoid persecution during World War II) made two documentary films about the plight of Spanish Republicans: Au secours du peuple catholique basque (Aid to the catholic Basque people) in 1937 and Un peuple attend in 1939. Interviewed in the late 1980s, Le Chanois explained that his second film was banned by the French authorities because of its depiction of concentration camps.

“I filmed the concentration camps of Argelès secretly, and as a Frenchman, the way men were treated on that beach still makes me feel ashamed,” Le Chanois said about his experiences filming in the south of France. “Years later I met a girl whose mother had helped me transport my hidden camera under the vegetables she was carrying in her bag. The living conditions were dreadful: thousands of men guarded by Moroccans in February and March without food, shelter, or medical care. Later, I went to a hospital in Perpignan where men were left lying on the steps, or lying on the floor in the wards. I also visited the places where women and children were sent; it was the most hostile area in France and they were locked up in derelict farms or houses in ruins. The women sang the most heart-rending songs.”

Although the negative of the longer film was destroyed by French authorities, members of the International Brigade were able to send a copy to the United States, where it was edited by Irving Lerner (in cooperation with the Franco-Communist company Ciné-Liberté) intended for North American audiences to spur relief efforts for Spanish Refugees in the wake of the war. However, due to political disagreements within SRRC and the lack of support after the end of the war, Refuge became the last large effort of the organization, which officially disbanded in 1940. The film went largely unseen. It was most likely shown in private or small meetings but never screened publicly.

The seeds of the postwar Red Scare were already sown, as the democratic cause of Spanish Republicans became inextricably linked with its Soviet communist benefactors in American eyes. When tactical support of communism and socialism was replaced by political fanaticism in the early days of the Cold War, Refuge and its cause were forgotten.

In 2001, Spanish film historian Magí Crussels discovered a video copy of a film preserved in the Museum of Modern Art in New York that was catalogued in archives in Spain. After some research and an in-depth analysis of the particular copy, it was discovered that this film was mistitled Un peuple attend after the original longer documentary but was indeed Refuge. The clips in this 27-minute edit are the only remnants of Le Chanois’s longer film. In 2009, Refuge received its first official public screening, 70 years after its original production.

An Historical Perspective

The Propaganda Machine Show aims to deconstruct the subtle shades of propaganda via cinema, chamber opera, and cabaret, from the advent of film as a political tool in the 1930s, to the heart of Fascism in Europe in the 1940s, to “fake news” today. In the century of the refugee, we use the first modern media coverage of refugees as a humanitarian media machine to remind us that we are all humans in search of the most basic necessities: a roof over our heads, some food to eat, and people to love and share it with.

We present Refuge with a newly commissioned score by Joshua Hartman, which brings a fresh perspective and continuity to the soundtrack of the original footage, much of which was poorly edited, accentuated by live narration. Part II of The Propaganda Machine Show will lead us in a very different direction into the fascist propaganda of the 1940s with the chamber opera Greenland (Kassof/Hut-Kono), in which I take a lead role. Part III presents a cabaret led and directed by Nicole Renna as a satirical conclusion, recalling the birth of a genre in the early 1920s as a positive consequence of war, where people from all walks of life could dress up to sing and lighten some heavy hearts with witty banter and cocktails.

If we cannot remember to become human again, to laugh, to smile, to love, our existence will crumble into the surreal reality of fake news. We cannot surrender to that mindset. We must continue to see our similarities despite our differences—from Spain to Palestine to Syria to Mexico to Yugoslavia to Rwanda to right here in Philadelphia. We are one world, one humanity, and we are our only refuge from ourselves.

— Anaïs Naharro-Murphy

What: The Propaganda Machine Show

When: September 10, 14, 17 + 21, 2018

Where: 1fiftyone gallery + artspace, 3312 Kensington Avenue

Cost: $20

Created by Evan Kassof / Anaïs Naharro-Murphy / Nicole Renna

FringeArts.com/8369

Photo at top courtesy of Olga Teresa Brocca Smith.