Happy Hour on the Fringe: Legal Tender with Kyle Dacuyan and Vanessa Maria Graber

Health and safety are our number one priorities here at FringeArts, and in compliance with CDC recommendations for staying safe during the Covid-19 pandemic, we will be postponing our 2020 High Pressure Fire Service presentations. More information will be available soon about when HPFS will take place. Happy Hour on the Fringe will continue to come out with podcast episodes about our artists and community partners, so don’t fear — FringeArts is still kicking! Community is crucial in this time of crisis, so please do not hesitate to reach out.

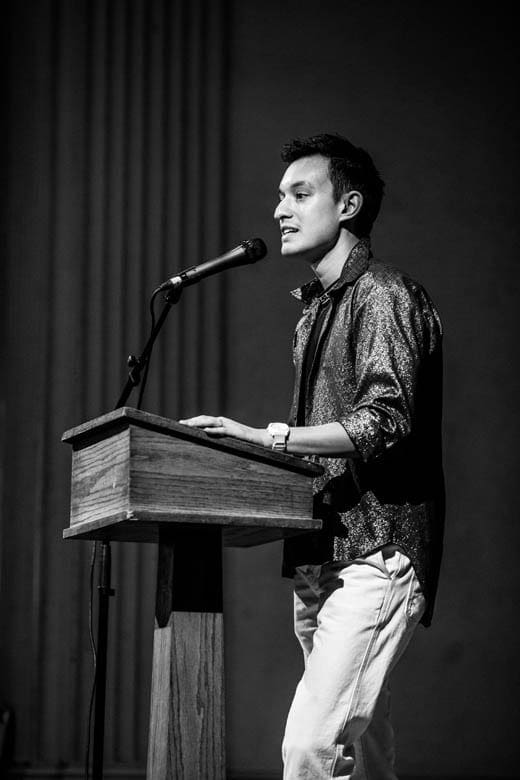

In this episode of Happy Hour on the Fringe, you’ll listen to a conversation about the themes and questions in the 2020 High Pressure Fire Service presentation Legal Tender by Antigravity Performance Project. For our HPFS episodes, we like to connect our artists to community members and advocates who are thinking about the same questions the artists explore in their HPFS pieces. This episode features a conversation between Legal Tender lead artist Kyle Dacuyan, Executive Director of The Poetry Project, and Vanessa Maria Graber, the WPPM Radio Station Manager at PhillyCAM, Philadelphia’s community access media center.

Listen to the episode and read the transcript below!

Tenara: Hello and welcome to Happy Hour on the Fringe. FringeArts is Philadelphia’s premier presenter of contemporary performing arts. My name is Tenara, and I’m the Community Engagement Manager at FringeArts. I invite you to pour one up and enjoy our conversations with some of the most imaginative people on this plane of existence. In this episode, you’re going to hear a conversation about the themes and questions in our upcoming High pressure Fire Service presentation Legal Tender by Antigravity Performance Project. For our HPFS episodes, we like to connect our artists to community members and advocates who are thinking about the same questions the artists explore in their HPFS pieces. Today’s episode features a conversation between Legal Tender and lead artist, Kyle Dacuyan, Executive Director of The Poetry Project. And Vanessa Maria Graber, the WPPM Radio Station Manager at PhillyCAM, Philadelphia’s Community Access Media center.

Vanessa is an organizer, social justice advocate, and media producer from Philadelphia. She has worked in the field of radio for the last 19 years at eight radio stations as a bilingual producer, news reporter, editor and promoter. Listen to this fascinating and urging conversation about media justice and literacy between two brilliant practitioners. And don’t forget to check out Legal Tender at FringeArts April 16th through 18th.

Kyle: Hi, Vanessa.

Vanessa: Hi, Kyle.

Kyle: I’m really glad to be talking with you today.

Vanessa: Likewise, it’s my pleasure to be here.

Kyle: Maybe as a place to just frame everything. I’m really excited about this performance that I’m working on that will happen at FringeArts in April. That’s focused on the relationship between personal information, media and news content that we produce and receive and how that shapes our understanding of different work in our communities around us, whether that relates to labor or orders or different kinds of activism. And I’m really excited to be talking with you today because I come at issues of media justice from an artistic practice and I feel really grateful to be talking with someone who’s coming at this from more of an activist and advocacy practice. Thanks for making the time and I’m excited to talk more about this with you.

Vanessa: Yeah. I’m excited to talk to you because it’s often that we are in our bubbles silo-ed doing our work and it’s always great to share and understand the different ways that people approaches through policy work, through organizing and in your case through the arts.

Kyle: Yeah. And I think that people who aren’t as involved in media justice work as either of us might not quickly understand or fully understand what that work encompasses. So I’m hoping that at some point in this conversation we might each be to say a little bit about what that means and looks like for each of us. And I was thinking that as a kind of entry point for us, maybe we could each say a little bit about how we got connected to media work in the first place and how that drew us even more deeply into it, specifically advocacy focus work around media.

Vanessa: I’ve always been superglued to television. I was born in the ’80s and like many people, my parents watched a lot of TV news and read the newspaper and listened to the radio. So it was always a part of my world. There’s several people that really inspired me. People like Lisa Thomas-Laury, was a local newscaster, and Christiane Amanpour, who was a foreign correspondent. And just the way that they told stories and because they were women and especially women of color that they represented people that weren’t normally shown on mainstream media. I started in high school at my TV news station, CDTV, and read the news to my fellow students. It was a pretty dorky thing to do, but I thought it was really cool. Not many schools had TV stations there.

Vanessa: I was fortunate to be at a high school where we could learn media and participate. So I was 13 years old and I engaged in other youth media programs over the summer. And so I always knew I wanted to go into media. When I went to college, I joined my college radio station and I really liked the relaxed nature of radio, where you didn’t have to worry so much about what you look like as long as you were playing good music and sounding good and there’s sort of a mysteriousness about radio broadcasters. But I really like. You could be anonymous even though you were a voice on the radio.

Kyle: In the year before I started putting together this performance piece, I was working in a role that had me traveling around to different communities and convening both media consumers and media producers. And something that I heard really frequently it was what you’re mentioning about radio, that the dimension of representation is really different because we’re not seeing who’s speaking, but that doesn’t mean that we don’t still get to have a sense of character of whoever’s delivering particular news in media. I’d love to know, when you started to feel tuned into issues of representation in media, was that something that you felt early on watching women of color on television? Or was it something that you maybe felt more and more conscious of once you started working on this in college?

Vanessa: I don’t think I was as aware because Philadelphia where I’m from, there’s a lot of Latinx media and I consumed a lot of Spanish-language media as a kid, watching Telemundo and Univision. And it wasn’t till I went to college in rural Western Pennsylvania that I found myself being one of the few Latino people. And not only at my university, but definitely in media. And so for that reason, myself and a friend started the first ever Spanish language radio show because there was a growing Mexican population in the area. And so we thought, “There’s literally no resources for them. Let’s just have a music show and do some international news and at least carve out a little space on the airwaves where people can tune in every week, so that there would be something that they could connect to.”

Vanessa: Around 2002, 2003, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were beginning. And I don’t think that the mainstream media was circulating information that was accurate. And in fact, many people believed a lot of myths and misinformation about the wars. And with respect to the muslim community, it was very obvious that they were being demonized and not represented, and also people on the ground in the Middle East their voices weren’t being heard. And that really affected me and I decided to get involved in anti-war organizing. And as I progressed through my activism, I realized the huge role that the media plays in all of that. And it was around that time that I discovered the independent media movement and the media reform movement where people were talking about these issues of representation, diversity, alternative media, different kinds of narratives, and how do we actually present the truth to the public?

Vanessa: And so again, it was this time where I was a student, I was an activist and I had began this journey of understanding how our stories, the way we present information can have these global impacts. And it took me out of local bubble that I had and into more of a global movement that not only advocated for peace, but advocated for representation and the ability to tell our own stories correctly.

Kyle: I would love to know more about what inside of media coverage around the war raised your consciousness here. Because I think a reason that I really passionate about media advocacy is because it’s so important to have information. It’s so important to have vetted information in order to participate in civic life, to advocate for different change that we believe in. And at the same time, I think most of us grow up with the conditioned expectation that what we hear and see in the news and in the media is factual.

Kyle: And so I’m always really eager to know what and how brings people to the recognition that media has all kinds of bias and incompletion and misrepresentation wrapped up inside of it. And that’s where I feel really important work, like you’re describing around the independent media movement, that’s where I think a lot of really necessary work needs to be happening especially right now. But I’d love to know, when you were absorbing news content in 2002, 2003, 2004, what were you observing that started to make you realize that we could be addressing media a little more critically and thinking with a little more of a critical perspective about how it gets made and what are all of the consequences of the ways that it gets made.

Vanessa: I did a three study abroads when I was in college and in grad school. During September 11th, I was actually in the Virgin Islands on St Thomas studying Caribbean journalism at the University of the Virgin Islands. And that was the first moment where I realized that there’s many different perspectives on US imperialism and war. And we were definitely in the minority. There was a lot of anti-American sentiment because islands like the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico are colonized by the US. And so the coverage and the narrative around war was really different. And it’s probably the first time I was really exposed to that because I had been in my own bubble in Philadelphia and in Western PA.

Vanessa: I also had done a study abroad in Costa Rica where again, the narrative of foreign policy and capitalism is really different than what I had learned about. And so when you’re talking to people while on traveling around the country, there’s just really a diversity of opinions and perceptions about the US’s role in other countries. So, I would say it wasn’t any one moment, but a journey I began to go on as I began to travel. And also I did a study abroad in Vienna, Austria, where many people scolded me for being an American and for voting for Bush and for supporting the war. And I would say like, “I didn’t vote for Bush and I don’t support Bush. Why do you think that?”

Vanessa: And they had explained to me that in their media that they had viewed Americans this way, that that’s the story that was being told. So I did describe to them the polarized nature of our country and that there’s actually a big anti-war movement. And so it was clear to me that their perceptions also were being shaped by media. Right? Because they had never been to the US. And it was only through this dialogue, talking to people, having an exchange that we were better able to understand each other. And so again, as I traveled throughout Europe, this kept happening. Again, people ask me very interesting questions about being American, being part of the United States and this issue of war. And so again, it really opened my eyes up to, “Wow, in the United States, if we don’t travel to other places, our only experience with the place, for example, is through media.”

Vanessa: And I remember going to Detroit for the first time and thinking like, “Detroit’s totally bombed out.” I remember watching 8 Mile, Eminem and I just thought all of Detroit was like that. And when I went and I saw that it’s actually on the waterfront and there was beautiful parks and a nice downtown area and some really beautiful urban farms, I was like, “This is not what I thought it was.” And so again, it was another moment where I was… Again, my perceptions were shaped by media, by film, by these things I had been exposed to.

Vanessa: As you continue to travel and see things for yourself and meet people and find out the real story, you begin to understand that you have a lot of unlearning to do and that we have a lot of personal biases that we come into with places that we have no real experience with. And so all of that culminated at wanting to be part of a solution and trying to address this and figure out ways that we can have alternative narratives and more representation. And so around that time is when I started to get involved with media justice and media reform.

Kyle: National media is so inclined to bring different kinds of bias into reporting, whether that’s national media reporting on other national experience like what you’re describing with Austrian media presentation of – limited Austrian media presentation of what the US experience is. And then I think there are also limitations around the ways that national mainstream media presents different local experience like what you’re describing with Detroit. And that’s part of why I think local media is so important because it’s really essential for people who are in specific communities to also have the resources and the platforms and the opportunities to be reporting information from within those communities. Already you’re describing how important travel is, and just passing through different places and recognizing that we live in different spheres of media, even when you were talking about growing up in Philadelphia where there was an abundance of Latinx media and then going to Western Pennsylvania where you were encountering people who hadn’t had that in their household before. And then describing what news coverage looked like in different nations where you were doing study abroad.

The ways that these little media spheres become enclosed bubbles and the ways that we fall into those bubbles unconsciously is something that I feel really attentive to and concerned about with passion. And I would love to know how you’re thinking about that today. When you think about the ways that media bubbles exist today, how does that feel different from the Iraq War era? I mean the early Iraq War era. With all the ways that we participate in social media, how our media sphere is becoming even more narrow, and at the same time, how our social media and online lives making information exchange open up in new ways that it hadn’t before.

Vanessa:

Yeah. So it’s almost like this paradox, right? Because of more internet access and social media and platforms like YouTube and smart phones and WhatsApp. We’re more interconnected than ever, information is more accessible than ever and it has really democratized information and media, which is great, right? We’re able to be part of the media. Anybody can be a citizen journalist or community media journalists or a blogger or have a YouTube channel and tell their story. And people are making movies on their iPhone, which I think is really rad. And now we have all these community radio stations all over the country. So there’s definitely been huge steps made in terms of access. At the same time, people can still be very vulnerable to disinformation and quote unquote fake news and memes. We often joke, “The real war is the meme war.” Right? Because people share memes and believe memes so much. So then they wouldn’t necessarily share a news article.

And so even though we’re more interconnected and more informed, there’re still so much noise and propaganda and disinformation. And we’re seeing the perforation of white supremacists platforms and hate speech and trolling. And so along with all of that access comes all of those negative things as well. So the work, the activism, it never stops. We’re still working and people might say, “Oh, but you’ve started all those radio stations, what are you working on now?” And it’s like, “Wow, that just because we now have maybe a platform, it doesn’t mean that we are stopping the work.” Because the reality is there’s still a lot of communities that don’t have access, there’s still censorship, there’s still a corporate media narrative that supports the status quo and doesn’t represent everybody.

And so we still have to continue fighting for more access to communication and for, again, that equity and media of which is making laws and policies and make it accessible to all, but also holding media journalists, creators of content countable as well. And that’s just not limited to news, we still have a film industry that excludes women and people of color. We still have a music industry that’s owned by just a handful of record labels. We still have books trying to tell Latinx stories by white people that are being promoted into the mainstream. So there’s still a lot of work to do even though we have a lot of access now.

Kyle: I hear and feels so tuned into so much of what you’re saying here. I do think that the proliferation of fraudulent news is really alarming. As part of the press freedom organization I was working with before, we had done a study on the extent of fraudulent news and in collaboration with Stanford found that during the 2016 election in an analysis of just the news content that was shared over Facebook, so this is one specific social media platform, the news content shared within the US over Facebook during the 2016 election, as part of this study came out from Pen America and Stanford, we found that more articles that were provably false or fraudulent. More of those articles were shared than articles that had acceptable vetting standards.

I would say I’ve always been tuned into media, but it was really the 2016 election that started getting me thinking about the extent to which we’re really hanging in the balance around the integrity of information. And so I feel enormously concerned that we have vast communities and networks who are forming alternative spheres of media and information. And I feel that an essential counter to this is local media and empowering local media to have the resources that they need to report and more deeply understand and more deeply respond to the information needs of their communities. And I would love to hear from you about beyond increasing access, which I agree we’ve done a lot of admirable work around, when you think about the ways that communities can be supportive of media advocacy and specifically advocacy for local media, what would you want people to know or feel to be more deeply connected and involved and supportive of their local media and environment?

Vanessa: Well, I think first and foremost, as media makers, as advocates, as a member of the community, we need to be more engaged and connected to our communities. We can’t be preaching these messages from the internet or from the halls of Congress. We have to really focus on building strong relationships and getting connected to people who have influence in various communities, and that means aligning with nonprofits and community leaders and artists. Right? Artists play a huge role in all of this. And I think that the more we are engaged in a human way, not in a virtual way, the more power that we can build on the ground. And I think that allows for these very real conversations to be heard.

You have people canvassing now for candidates that I’ve probably never been to these communities who are not maybe of the same demographic, trying to convince them to vote for a certain candidate. And statistically, that has some sort of efficacy. Right? But what would be more effective is people from that communities speaking to their neighbors and their family and friends and having conversations with them about their values and what the needs of their community are and which candidate might best serve those needs. As media, I see a lot of journalists even exploit communities and then they want them to be engaged and they want them to consume. And what I’ve learned through community organizing is that you can’t get people to support what you’re doing if you’re not in solidarity with what they’re doing. So that means supporting the other movements showing up for the community when the community needs people listening and being present when it means that you’re not getting anything out of it, and being somebody who’s just civically engaged, you have to be a good citizen.

You’re close than your neighborhood if you want people to be engaged with you and with what you’re doing. I love being part of community media because this is really first and foremost of everything that we do, it’s finding ways to be in and have the community understand what people’s needs are, find out what they’re doing, supporting their events, and making things free and accessible. Right? I think there’s this ethos that we have about understanding that not everybody has the means to pay for things all the time. And so the way that we’ve been able to build a movement is by being like I said in solidarity with other movements and having this clear line of communication, having people on the ground and then when you need something, when the time comes, you already have a mobilized, engaged people power to be able to implement the thing that you want.

When it comes time to advocating things like public access television, net neutrality, funding for public media, you can’t just snap your fingers and expect people to support those things if you haven’t been visible in their communities, and be building relationships with the people that matter. And so I think that’s part of the way that I approach things in terms of getting people to do the thing that I want, right? It happens over a long period of time, and it takes a lot of hours of participation. It can’t just be about your movement and your issue. All the issues are intersectional, and I think again, then there’s this exchange, right? So when there’s other calls to action for other things, we all must also be present and be ready to support.

Kyle: From what you’re saying here, I’m remembering this experience I had about a year and a half ago or so of being in Southern Ohio, and we had done two community convenings with journalists in Southern Ohio and Northern Kentucky who were writing about the opioid epidemic. And we had one convening that was really clearly a predominantly white audience, and we had one convening that was really predominantly a black audience. And there was a lot of frustration from the black community in this meeting about the ways that they felt journalists, mostly white journalists working for the main Ohio publication, ways that they felt these journalists had really neglected the particular dimensions of the opioid epidemic for the black community. And the ways that historically the black community had been totally differently villainized around substance abuse and addiction issues, which are health issues.

There’s a lot of frustration in this meeting and the response from the journalists was, “There are opportunities for you to become information providers to local journalists. We should be thinking about how you can situate yourselves as experts, people who have really valuable, necessary information to share with your local journalists.” And I remember one person in the audience saying, “What if no one believes me? And what if I have no credibility because of how they see me?” I think about that moment so frequently. And I’m wondering if you have… We’re talking from the perspective of what news makers and media producers and journalists, what responsibilities they have to better support the particular needs of their audiences, but I’m wondering if you have recommendations for how people in different marginalized communities might be able to get some empowerment. How do disempowered constituencies work to get media just more leveraged and more responsive to their particular needs?

Vanessa: I mean, obviously I work in independent and community media. So our approach is to make our own media and that’s the opportunity that we give people. Like, “Listen, you are not being represented and your stories are not being told. Right?” And I don’t know if we can change that with the current corporate media structure, but we can provide alternatives and we can tell our own stories. I think now more than ever, there is an effort towards community engagement and collaborative journalism and you’re seeing a lot of that here locally where there are other institutions like foundations and universities who are trying to bring journalists together across platforms to have these important conversations. It’s going to take some time. In the community radio movement and even public access TV, we couldn’t wait any longer for them to do it. So part of what we were doing is taking the airwaves back and putting the media back into people’s hands.

And where I work now, before we had a radio station, there was a real void on the airwaves in terms of having a diversity of voices. Now, there’s five new stations, at my station, there’s over 80 producers, there’s over 60 programs and we’re doing it ourselves. We’re telling our own stories, we’re creating another narrative, we’re promoting an alternative. But I would also say we can’t let up the pressure and accountability of those other sources of media. And that we should continue to try to engage journalists and institutions and demand better coverage and accountability.

I also think that community media is very interested in working with artists and telling these stories through other ways, through music, through poetry, through film, through the performing arts. And we’ve had so much success and interest when we partner with arts organizations and when we go to festivals out in the community and when we do local music, concerts and open mics. I mean not everything is totally new story. That’s not appealing to everybody. And so finding ways to use the arts as a vehicle to deliver these messages using satire and comedy, I think those are also super effective tools and I see just so much opportunity and being able to work together, again, to just provide an alternative to what’s currently being offered.

Kyle: Yes. Definitely, I hope so. I think that there’s a really important educational component that there’re important opportunities for community convenings and trainings and those sorts of things. But I also feel that when people are engaging with some kind of artistic experience, whether that’s a performance or a piece of literature or poetry or comedy or visual art, it hits us in a different way. And one of the reasons this topic feels so relevant to my artistic practice right now is that I think for the most part, like we were saying earlier, a lot of us just take for granted the particular spheres and bubbles of media that we live in. I’m wondering if you think there’s anything we can do to encourage people in our lives and in our communities to think more critically about the narrowness or breadth of media that they’re engaging with. Are there things we can do to get people to feel more enthusiastic about making a broader diversity of media part of the ways that they engage with and reflect around information?

Vanessa: Right. If I am watching a really good series on Netflix and I’m super excited about it, I’m pretty likely to tell a friend and say, “Oh, my gosh, I just watched this. I’ve binge watched it over the weekend. It was awesome. You got to check it out too.” And I think word of mouth marketing is probably the most effective, right? If I see a show and it was amazing and I say, “You have to check out this band, they’re so good.” I might make them a playlist or send them a link. Right? And so that’s what I do with people who I think need to have maybe changed your media diet. I recommend something that I think is really good and might be really helpful. And so I often share my own show, People Power, but I share things like Democracy Now or the Daily Show or sites like The Intercept.

I make those recommendations along with, “Here’s a great recipe for baked potato soup, right? So it’s like we’re always making these recommendations and doing word of mouth things. I really encourage people to change their media diet, to try new sites, to try new people and mix it up a little bit, right? Don’t stay watching the same show or be on the same newspaper site. With my students at Temple, part of their assignment every week is that they have to look at international news stories and they have to figure out what happened by using a diversity of sources. And in their groups, they begin to understand the different ways certain countries cover things or media outlets cover things. And they’ll say, “Oh, well, this media outlet said this, but this other outlet said this.”

And so they begin to learn like, “Oh, okay, I can’t just look at one site in order to get the story, I got to have a couple sources.” And so that’s what I recommend we do. Share those things that we think are effective and are truthful and would be good sources of information. I also think that we’re in this culture of shaming people online and I think that if someone shares a misinformation or a meme or something that’s not really true or very bias, I think the best thing to do is have a private conversation with somebody and not shame them, but understand, “Where did you get that information? Why did you think to share it? Hey, did you know here’s another piece of information.” Because it’s shaming of people who really don’t know and they’re not really intentionally trying to cause harm. That really causes people to get upset and disengage.

And so what we want to do is have a conversation and dialogue about it in a way that’s helpful and not making somebody feel bad because they may not be as media literate as you. I do feel that people need to chill out a little bit. If my mom shares a meme, I’m really like, “Hey mom, where do you get that?” And so again, it’s giving people the benefit of the doubt, I think goes a long way. So again, those are my two things. Share the things with people that you think will help them and keep doing it over time. And also if people do share misinformation, call them on it, but do it in a way that is not going to cause them to unfriend you or block you.

Kyle: I think both of the points you’re making are so important and I want to open them up in a little bit on a particular direction. I think that we can all always become more media literate and we can all be expanding our media diet. We can all be doing that. And what you’re saying about just how important the person to person relationship is, that feels so essential. But you’re also saying about exercising a little more gentleness in directing people to think about why they share or believe in something that feels so important.

And it feels like we’re just opening into a question that I don’t think that we can answer right now on it, but it feels like an important ongoing question, which is how can we reach people who are maybe living in a totally oppositional realm of media? How do we get people who are only consuming Breitbart and InfoWars and Fox News, for example, to engage with something with a little more breadth? That question feels challenging, but also really important and I personally want to be thinking about how to approach that in a way that’s not necessarily antagonistic or shame driven. I’m curious to know what you think about that.

Vanessa: Well, I think it’s going to be hard to reach those people. And I’m not sure if they’re ready to listen to somebody like me, but I do think that offering these free programs, having community forums, having these opportunities to connect in real life to be able to share things. I mean there’s been plenty of times where I’ve connected with people that we’re on opposite sides of the political spectrum, but maybe we were at a restaurant together or sitting at a bar together having a beer, and I think just try to be open minded to people that are different from you. And don’t isolate yourself into silos where you’re not going to come across a variety of different people. Get out to different cultural events, try things outside of your neighborhood, go to things that might challenge your perspective on things if not just to listen.

And I think that’s the main thing is just to get out of your own box, right? You can’t expect people to get out of theirs if you don’t get out of yours. Philly has so many events all around the year where there’s a diversity of people and you never know who you might be talking to. So just be kind, right? Kindness goes a long way and I think people are more willing to listen to you or have compassion for you if you show kindness, compassion and love. And I think at the root of all of my activism and everything that I do is just having love for our neighbors, our fellow people. And even though somebody might tune into those things, it doesn’t mean that they might be disrespectful to me in real life and we potentially could have a really great conversation and that could change both of us.

Try to keep an open mind, but also if you feel that you’re going to be harmed or experience some type of harassment, then do what you need to do to step away from that situation as well. Especially people of color, right? I think people of privilege, if you have education, if you have money, if you are white, there’s lots of privileges, use that privilege to reach those people for those who are marginalized and would not be able to navigate those spaces in the same way.

Kyle: Definitely. Vanessa, it’s been so good to talk with you. I hope that we can talk more another time.

Vanessa: Yes. I look forward to your event. And I hope that we could have more conversations like this between artists and activists because I think that we have a lot to share and a lot to learn from one another.

Kyle: I agree it. So Legal Tender is April 16th through 18th at FringeArts. Vanessa, are there any upcoming events or programs that you want to share with folks?

Vanessa: Well, I do want to advocate for people who are interested in anything that I said to visit PhillyCAM. We have a website, phillycam.org and we teach people how to make media. And we have a television station and a community radio station and lots of classes. And I think that if you’re somebody who has a story and you want to tell it, but just don’t know how, we have the space and the means for you to do that. So it is a open door for everybody who wants to do something creative and to have an impact in their community.

Tenara:

Thank you for joining us for this episode of Happy Hour on the Fringe. On April 16th through 18th, you can join us for Legal Tender by Antigravity Performance Project. In this trance-induced travelog, drawing from extensive conversations around our eroding news and media environments. We follow poet Kyle Dacuyan through psychic terrain and nightlife, family history and local communities, as he looks into the places where fact, opinion, and falsehood settle in us subconsciously. You can visit our website, www.fringearts.com for tickets. Make sure to follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, and Instagram and download the FringeArts app.